The past is a strange thing. It has passed, but is still present. What happened happened, and yet we cannot stop worrying about it. It is made present again and again, interpreted, re-interpreted, mastered, rejected, distanced, brought closer, deified, made specific, and melted. If we forget it, however, it remains as a worrying factor. It even makes itself present, often against our will (…). It can weigh on our shoulders like a burden which we would gladly throw off. Yet we cannot do this. It is a part of our selves. We cannot live without it. It has to serve life. Does such a thing exist? And if, being distanced, it is no longer such, can we make it serve life? Do we make it such? And when we make it such, what then happens to it?

–Jörn Rüsen

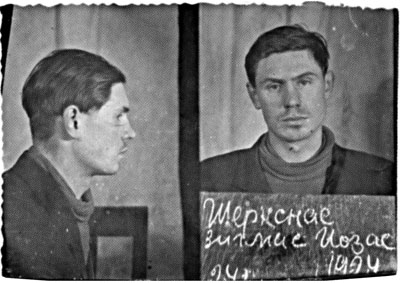

Death Diaries reveals something about the citizens of the Republic of Lithuania who suffered from the first Soviet occupation (15 June 1940 – 22 June 1941): Poles, Lithuanians, Russians, Tartars, and Jews – the innocent victims of torture, execution, and deportation to the gulag. This is an exhibition about their shattered lives and sundered destinies, about death and the absurdity of killing.

For several years, Kęstutis Grigaliūnas has been interested in ‘mug-shot’ photography used by different repressive institutions. The artist’s research for Death Diaries was triggered by a publication of the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, Lietuvos gyventojų genocido I-asis tomas: 1939-1941, a record of 30,461 people who suffered under the Soviet occupation. Because of that study’s magnitude, Grigaliūnas narrowed down his search to photographs in the Lithuanian Special Archives of those who were shot, tortured to death or died in exile, which have become the basis of the exhibition. The works have been printed using a silk-screen technique. The artist has handwritten a short biography of the person represented on each of the images.

Image: Kęstutis Grigaliūnas. Death Diaries. 2010