Rosemarie Trockel (b. 1952 in Schwerte, Germany) is among the most famous German artists, as important as Sigmar Polke, Georg Baselitz or Gerhard Richter. Although when she started her career in the 1980s the art scene was dominated by men, the viewpoints of her older colleagues became the starting point and the object of criticism for this rising artist. Rosemarie Trockel‘s art is open and critical, committed to social and feminist ideas. However, her works appear to the viewer as conceptual constructions, full of imagination and expression, smooth and convincing works of art. The artist is able to render even the most complicated intellectual problems with slight irony, thus avoiding heavy, dogmatic oppositions. According to her critics, while working, she is able to make one step away from herself and look at the creating woman with all the clichés permeating the atmosphere of the times and visible from outside. At the same time her art is an example of well developed craft.. In her works, a woman creating the image of nature remains a better or worse hidden pretext for irony and questioning of culture. While developing her work into diverse directions and using various means simultaneously, Rosemarie Trockel keeps following the same line of issues and, in some works, she as if finds answers to the questions she raises, in others she questions her own former statements, thus not staying in her permanent doubt, but going deep into the situation around her.

In a Lithuanian context the exhibition of this artist‘s work does not only fill one more gap in the visual education of art history, but also approaches a very important parallel to the art processes in Lithuania during the last decades by contrasting them and indicating common points of their issues.

Comments on Rosemarie Trockel‘s work

‘Rosemarie Trockel claims to see the world as a scale of samples, each action corresponding to archetypal thinking or behaviour, patterns. Everything is interrelated and those relationships are resilient. This reflection is founded on the skillful choice of materials, media and symbols. Her works betray her interest in social relationships. Gender issues, relationship between humans and nature as well as the phenomena of perception are important for her.’ (From the magazine DU, No.725, April, 2002, the issue dedicated to Rosemarie Trockel‘s work).

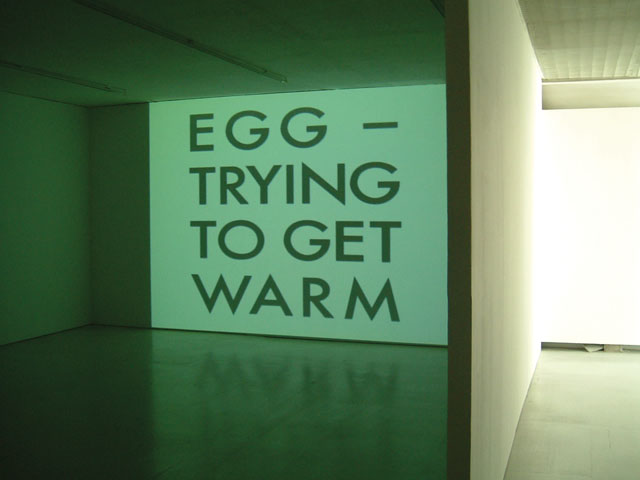

‘Rosemarie Trockel creates video art and photography, she also uses steel, plaster, fabrics and bronze, wool, wood or aluminium. She applies pencil, electronic equipment or the top of an electric stove, wool – which made her famous by the way – or hair and wax; actors, mosquitoes, caterpillars and silver exuviae participate in her works. She uses eggs in her installations or sprays milk with a compressor into a museum‘s premises. She “speaks” about things through things, which shake our consciousness as Jean-Christophes Ammann has once said. However, none of the materials is privileged in her works. It is chosen following the intention of the artwork. Rosemarie Trockel avoids using always the same materials, that is she avoids to create a “Rosemarie Trockel” brand name due to the easily recognisable repetitive choice of materials and style.’ (Nadine Olonetzky)

‘Rosemarie Trockel‘s art has many faces, she speaks many languages and feels a variety of levels of tone. Through irony or poetry, observation or division the artist performs a certain search in her paintings, sculptures, objects, installations and video art, which puts into the focus of the gaze what is gaze itself. The question what is being observed in a specific case is always related how the gaze at what is being observed gets formed.’ (…)

‘Rosemarie Trockel‘s works always thematise structures of the gaze, its deformation and especially blindness. In a culture, which is more and more deeply and quickly visualised, the gaze becomes an instrument of power. What comes in view, exists. However, what meaning acquires what is observed depends on how one is looking.”

“The images of the situation we are trying to record will always remain blurred. In such attempts Rosemarie Trockel creates the language of images, which does not confront, but fathoms out. Finally to intuit and not only know – this was the title of Rosemarie Trockel‘s exhibition an MOMA in New York. What sounded as only a programme in the 1980s, today obtained various shapes. All those blurred or empty spaces in her works are a conscious attempt to avoid absolute power – both of the eye and of the soul.’ (Ursula Sinnreich)