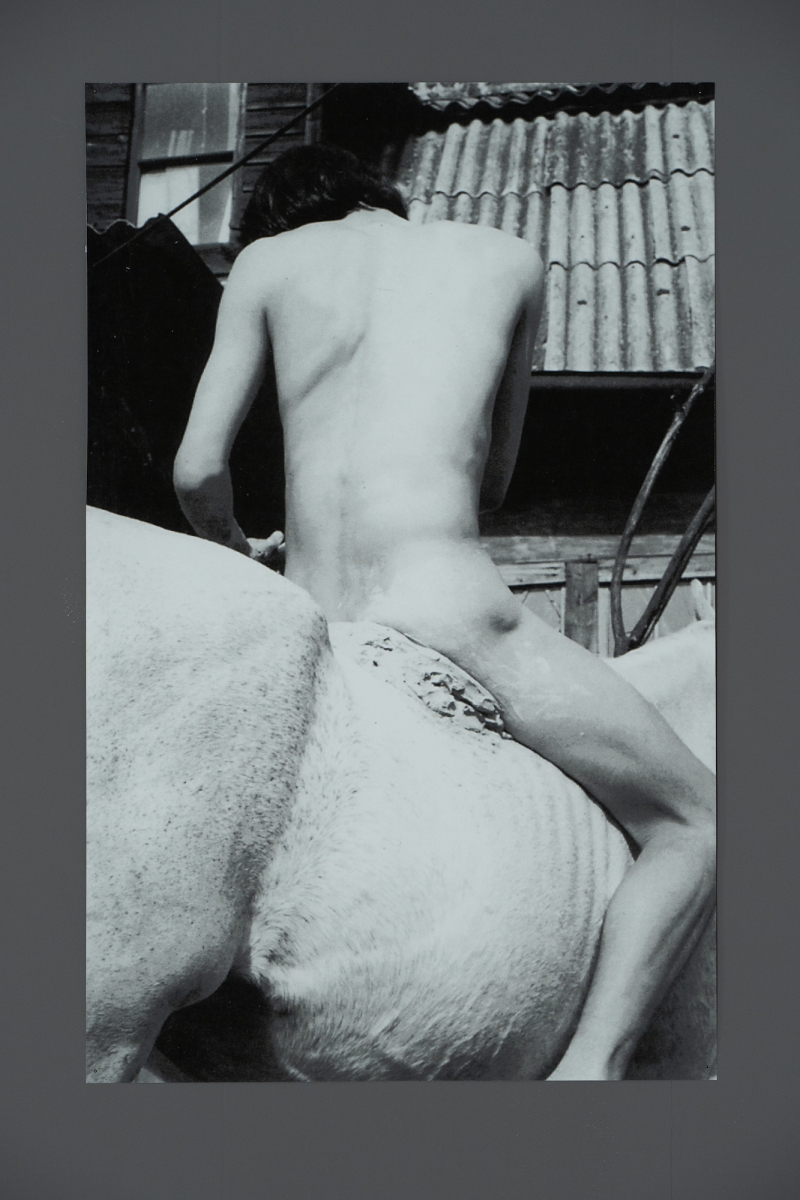

Radical art today is synonymous with dark art; its primary colour is black.

– Theodor W. Adorno

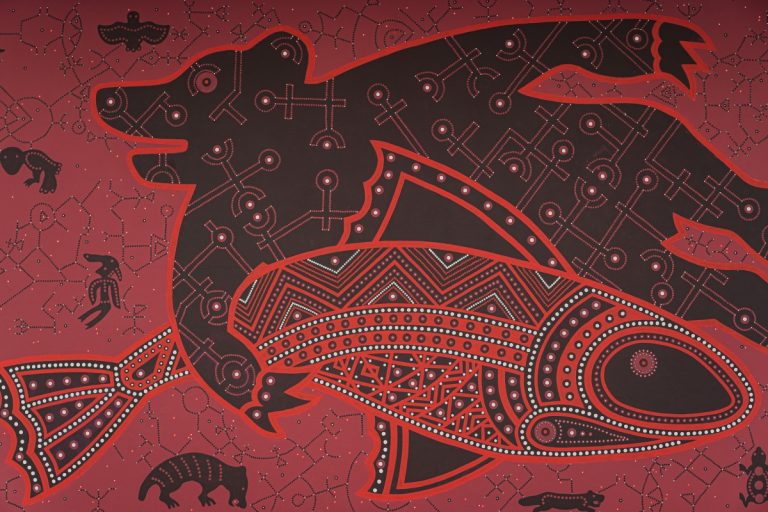

Blut und Boden was a key tenet of Nazi ideology. “Blood and Soil” was not just about stealing other people’s land and food; it was a mental crystal of feel-good darkness, a deviously emotional mobilising call in the “severe style” of contempt for the Other that melted so many twentieth-century hearts, not just in Germany.

“Blood and Soil” still melts the hearts of those who live in fear of humiliation by those whom they, in turn, hold in explicit contempt. The broader fear today is that violent conflicts between humans will be the outcome of human violence against nature. One cursory look at the state of the world is enough to realise that these are not mere dystopian musings.

The exhibition title reveals these three dangerous words (because “and” is never as innocuous as it might seem) as lethal poetic weapons rather than as blunt conceptual tools. This, by the way, was precisely how Nazi ideology worked. Yet “Blood and Soil: Dark Arts for Dark Times” repurposes the hateful slogan to serve another agenda, one of preservation and development rather than destruction and violence.

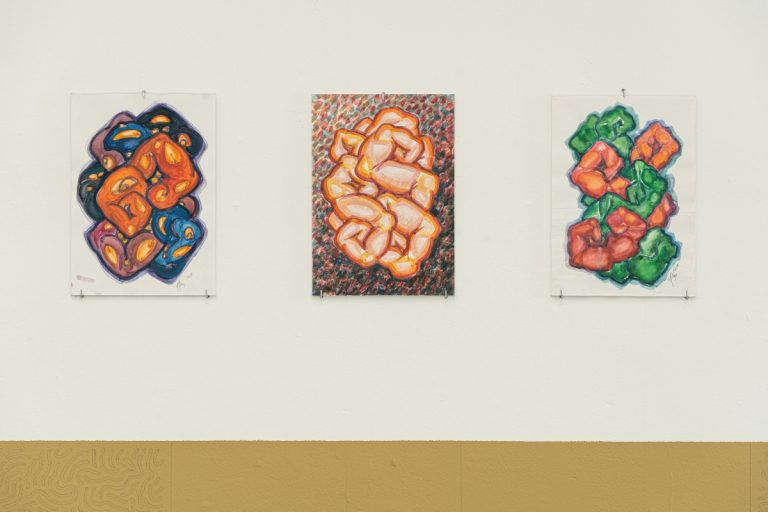

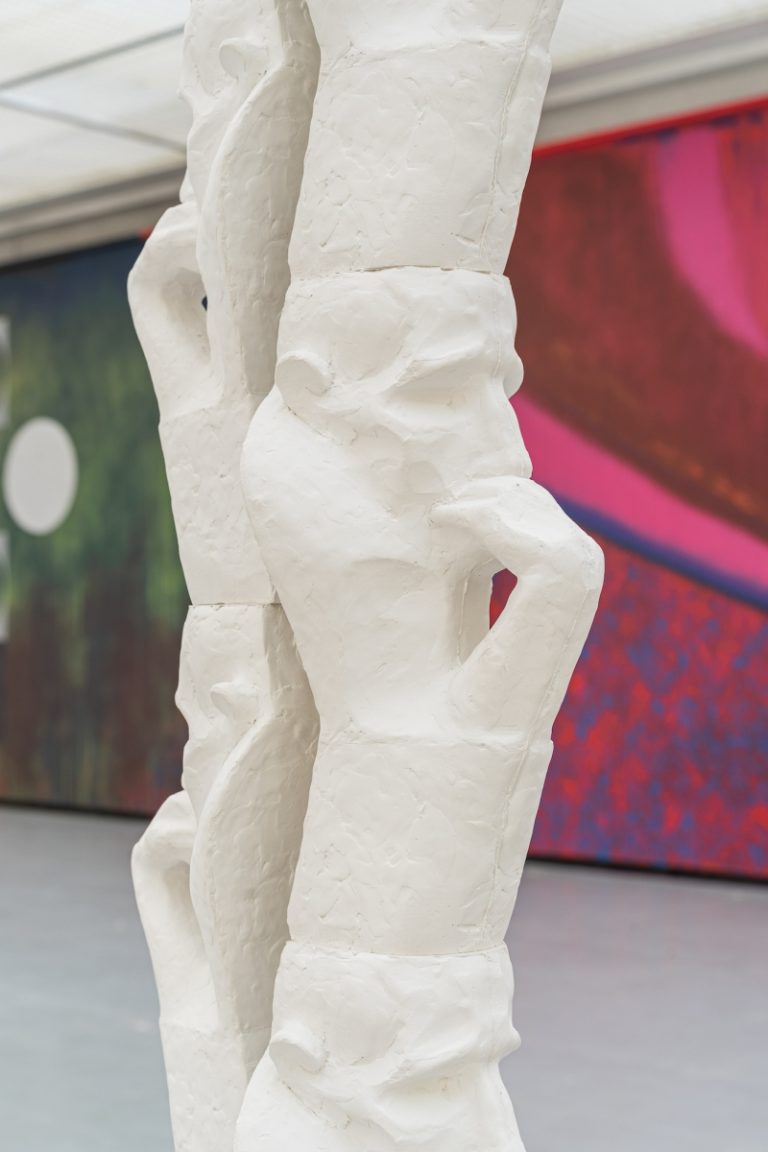

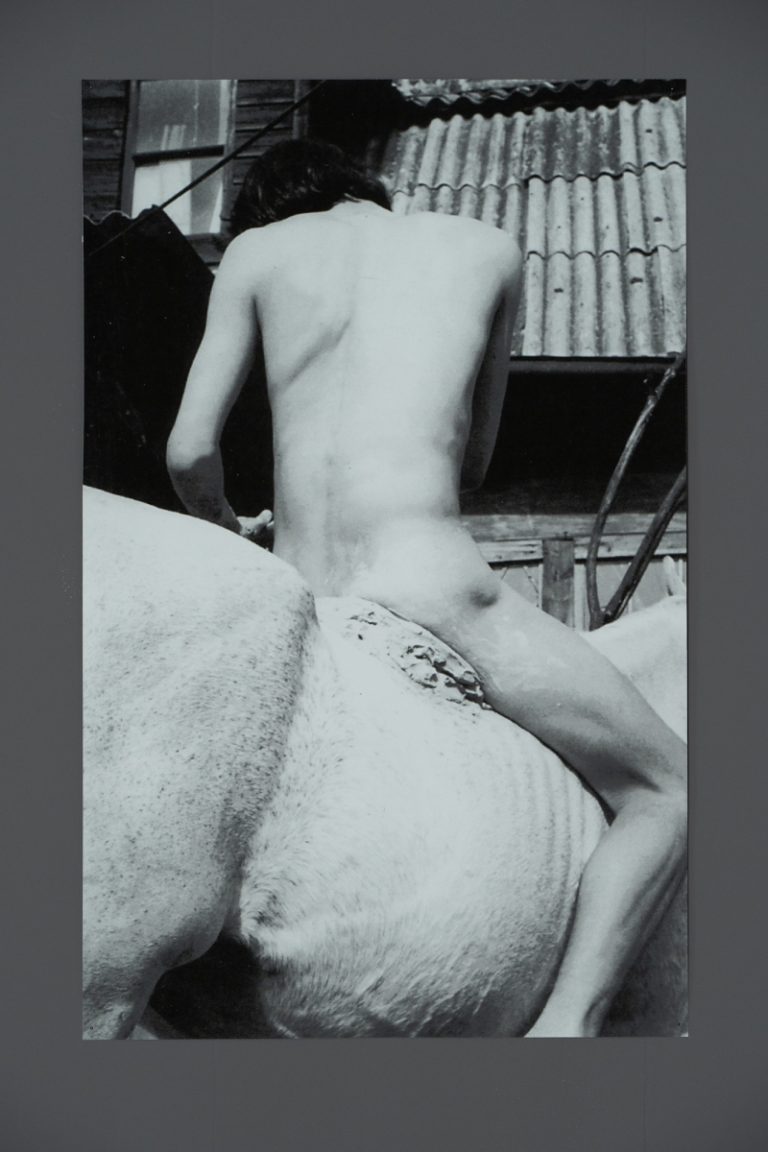

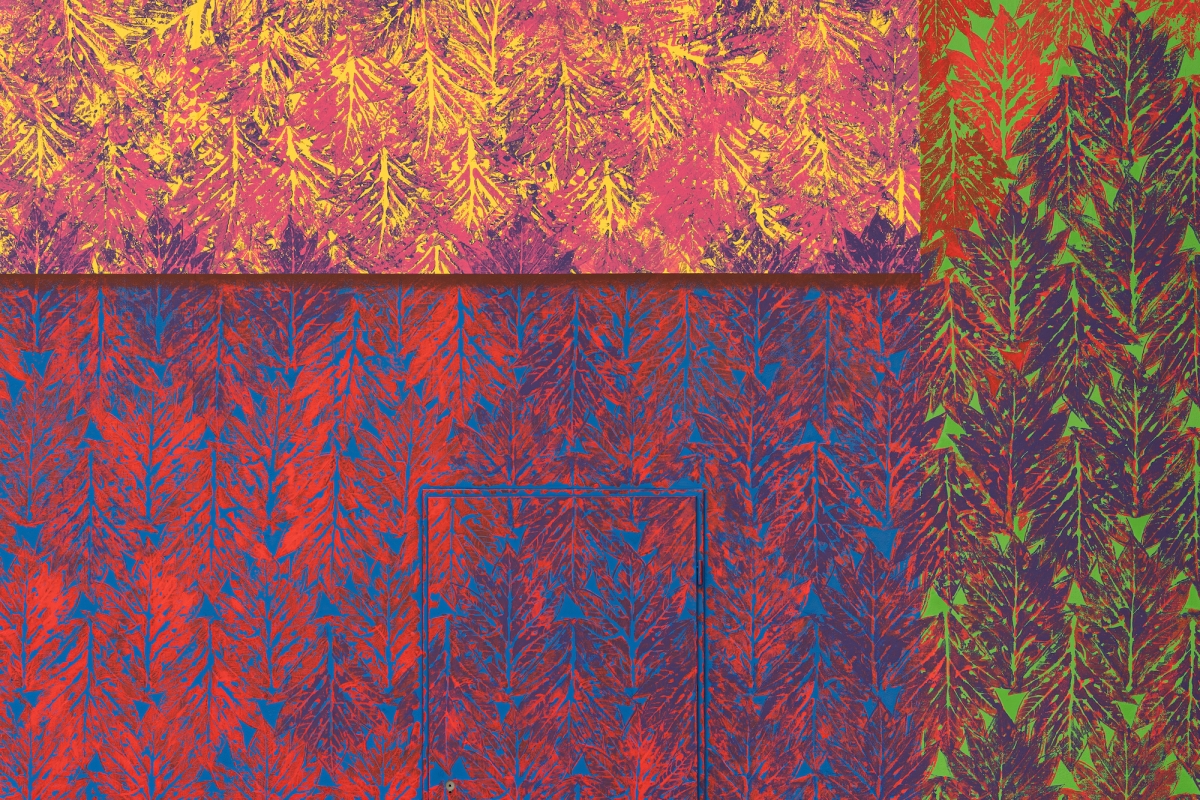

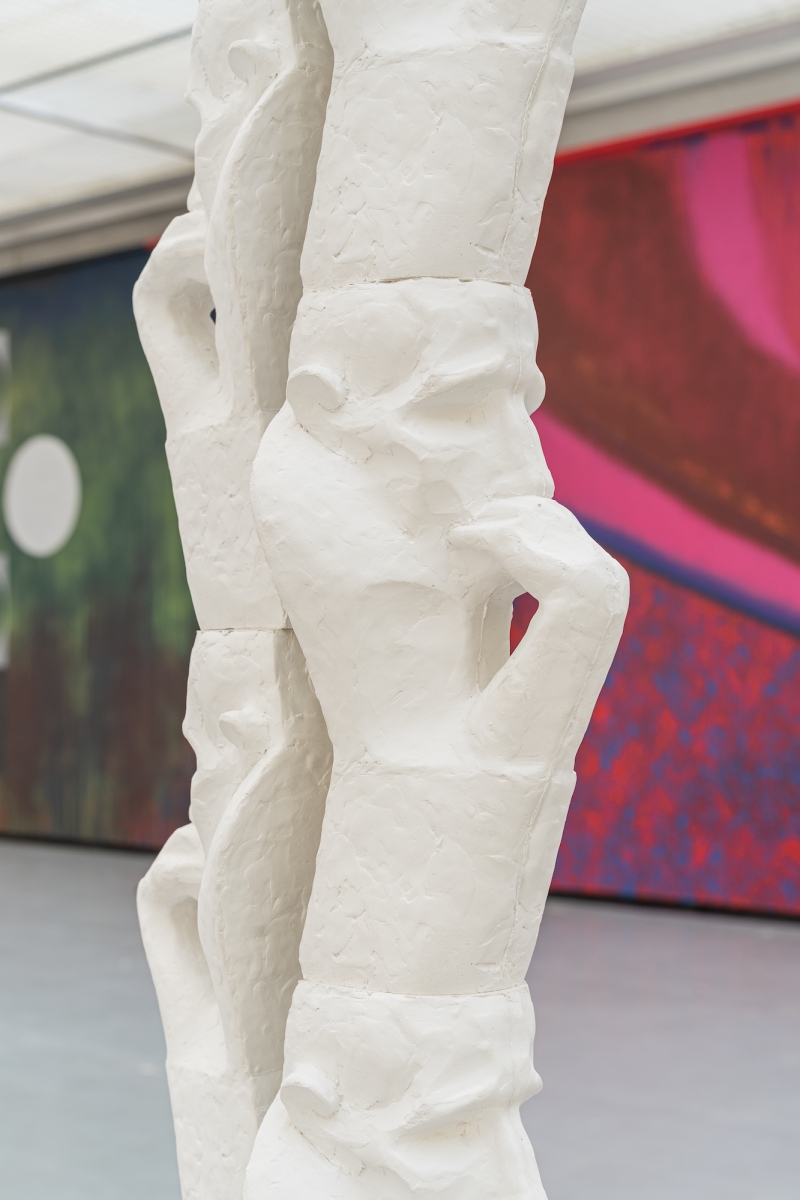

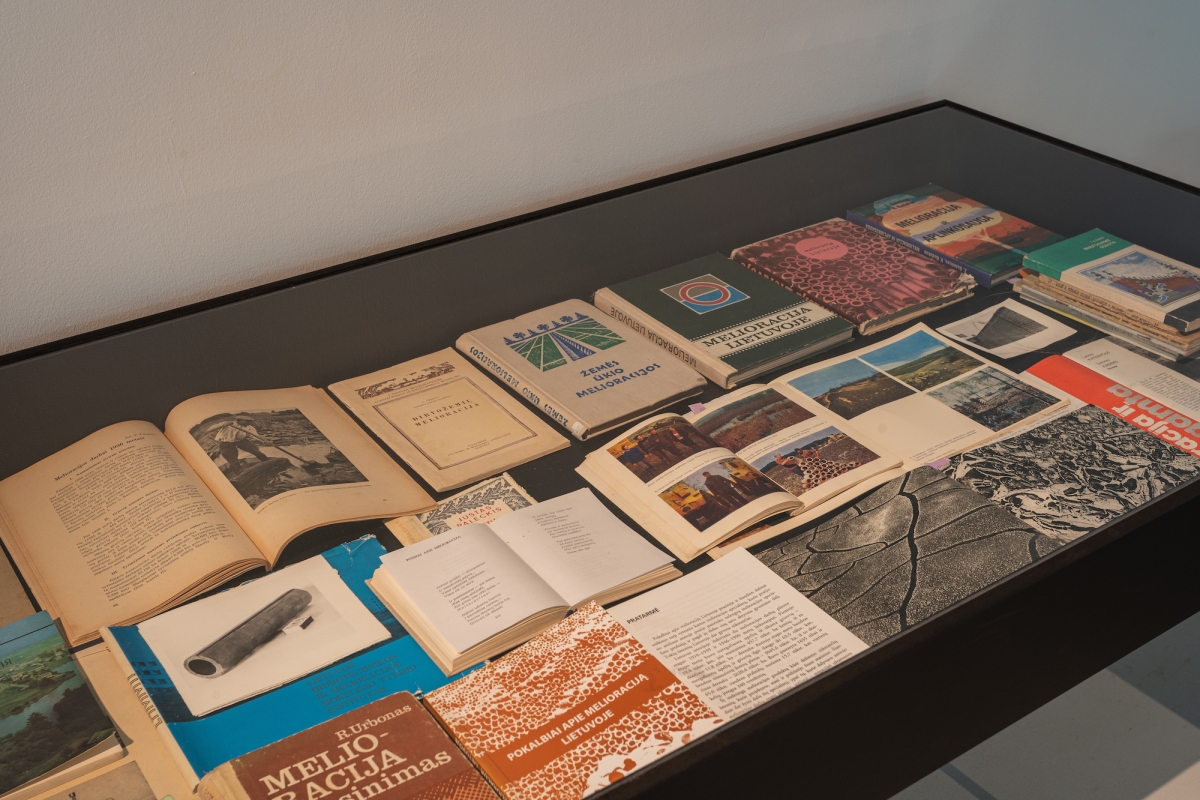

The exhibition is both metaphorical and visual, both “Eurasian” and “internationalist”, both down-to-earth and ephemeral. It does not attempt to “produce knowledge” or “raise awareness” or “chart territories”. Instead it relies on the determination of the participating artists to divert and subvert any curatorial agenda through their mind-opening practices. It suggests that painting may create spaces for thought, that film does more than entertain or communicate ideas and that performance is a suitable medium for telling multi-dimensional stories.

The “dark arts” of the subtitle should be understood as dialectically related to the tradition of enlightenment (a critical reappraisal of it) rather than as diametrically opposed to it (an affirmation of what is sometimes ironically called “endarkenment”). It is only by acknowledging the darkness behind the shining façades of contemporary life that we can start moving towards the light.

How can we, the still-privileged inhabitants of 2019, stay loyal to culture, as the articulation of what is inalienably human, in a world that needs us to do everything we can to preserve what is inalienably natural? How can we become truly terrestrial – which goes far beyond flying less or using less plastic or eating less meat – without giving up cultural values and skills such as literacy, the power of ironic observation or enjoying form without succumbing to formalism?