Aidas Bareikis (b. 1967 in Vilnius) studied painting at the Vilnius Academy of Arts. Following graduation in 1993, he went to Hunter College in New York with a Fulbright grant, where he received a M.A. in 1997.

Bareikis has had solo shows at Leo Koenig Inc gallery in New York, Center for Contemporary Art in Berlin, took part in many group shows in such famous institutions as P.S.1 Contemporary Art Centre/ MoMA in New York and various galleries in the United States and Europe including Eleni Koroneou gallery, Athens; Queens Museum, New York; Asbaek gallery, Copenhagen; Miller Durazo gallery, Los Angeles.

Visitors of the Contemporary Art Centre will be familiar with Aidas Bareikis’ works from the exhibitions ‘After Painting’, 1998; the Soros Fund annual exhibition ‘For Beauty’, 1995. The year 1992 was no less important – in that year the Contemporary Art Centre was established, and Aidas Bareikis (at that time a student of Kęstutis Zapkus) participated in the exhibition ‘Good Evils’. The artist now returns to the same venue ten years later for his solo show ‘Glad to Hear from You’. It is a symbolic commemoration of not only the artist’s career, but also the existence of the CAC.

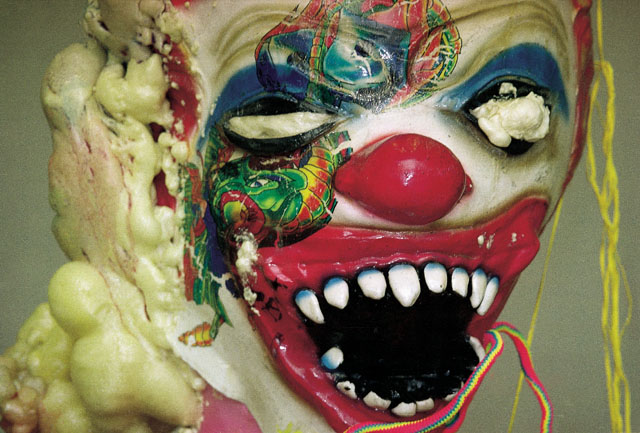

‘Glad to Hear from You’ is Aidas Bareikis’ new installation created for his solo show at the CAC. Having collected the material for his installation in Lithuania, the artist has created a plot imbued with the dramatics of The Monument to the Burghers of Calais by Auguste Rodin (1889). Aidas Bareikis’ original commentary on art history is sublimated to a chromatic cry, post-apocalyptic chaos, entropic mass so typical of the artist… However, unlike Bareikis’ previous works, this installation is less formless and more figurative in the Rodinesque sense. Prepared phantoms, as if drowned in the remains of civilization, associatively suggest gloomy thoughts about contemporary violence and terrorism. A dump of various objects (mainly used for games) scattered near ghost-like figures celebrates a politicised feast of life and death in a company ironically entitled ‘Glad to Hear from You’.

According to Rachel Kushner: ‘Consistently, traces of meaning-making mechanisms range from personal anecdote supplied by the artist, art historical references and the poetics of titles, to the sociological connotations of technology, the future, and trash. But these things – manifested as intimations of a post-apocalyptic condition, chaos, the slippery idea of formlessness, and less abstractly, sci-fi tropes, post-Soviet mayhem, war, Rococo, and the bedlam of consumerism – bob up, are drowned out by their own unstable, self-negating structure, and then once again resurface. Overall, there is fluidity from assemblage to assemblage, if only in the contradiction of fractured, almost schizophrenic barrages of meaning somehow warped into chromatic unity. But amidst the mess, such contradictions are tidily mirrored by our own: what is anxiety inducing also manages to entrance’.