In the New Yorker article dedicated to the premier of the tenth season of The X-Files, a hit television series of the 90s*, Joshua Rothman relates the rebirth in popularity of retro-futurism with the confused political policies of the current age, and our anticipation of global catastrophes. In Rothman’s view, which has been shaped by his own admiration for The X-Files, we not only long for a return to the delicate flirtation between Scully and Mulder (two FBI agents and the main protagonists of the series), but also for their old-fashioned fears, which, embedded, as they are, in a world without economical disasters and/or social struggles, provide us with a sense of stability and of a timeless state of being. In Rothman’s opinion, the foci of most current sci-fi narratives are social and/or economical difficulties, which are far scarier than the alien attacks or surreal visions of biological transformation that were so popular in the past. If all of this serves to make retro-futurism attractive, then it might explain the recent flood of remakes of sci-fi films of the 80’s, such as Star Trek, Star Wars and Mad Max amongst many others (the new TV series Stranger Things could also be evidence of our fascination with past futures). However, according to Rothman, aliens in themselves are less alluring today because they do not propose a convincing alternative to the scary future that is already anticipated in our present, and, as such, the adventures of heroes in a post-scarcity world are far more attractive. After calling The X-Files a purely retrofuturist work, one with a clear debt to the sci-fi of the 40s and 50s, Rothman asks rhetorically: what do our love and nostalgia for the visions and dreams of the past mean, and can we talk about having nostalgia for retrofoturism itself?

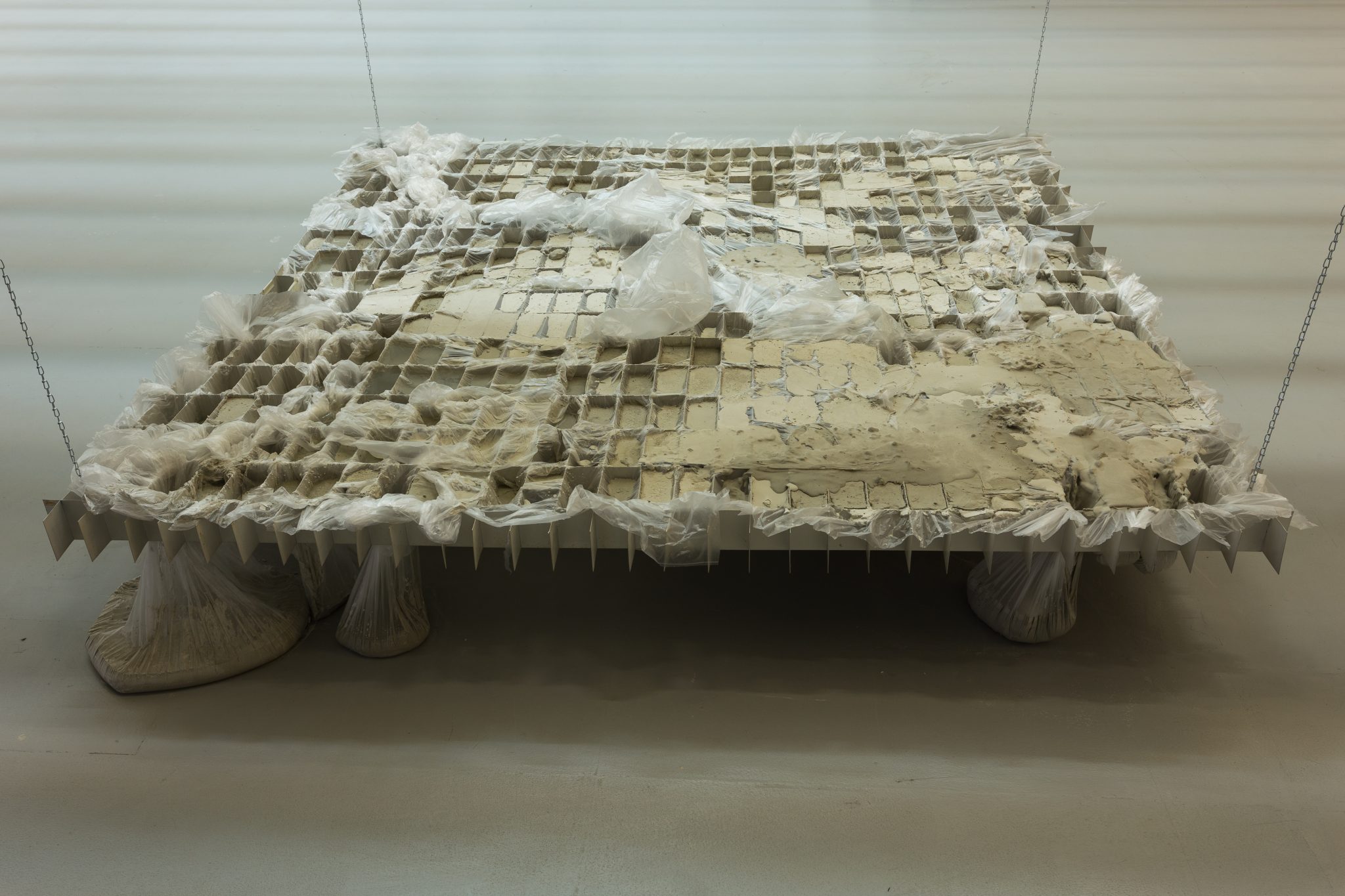

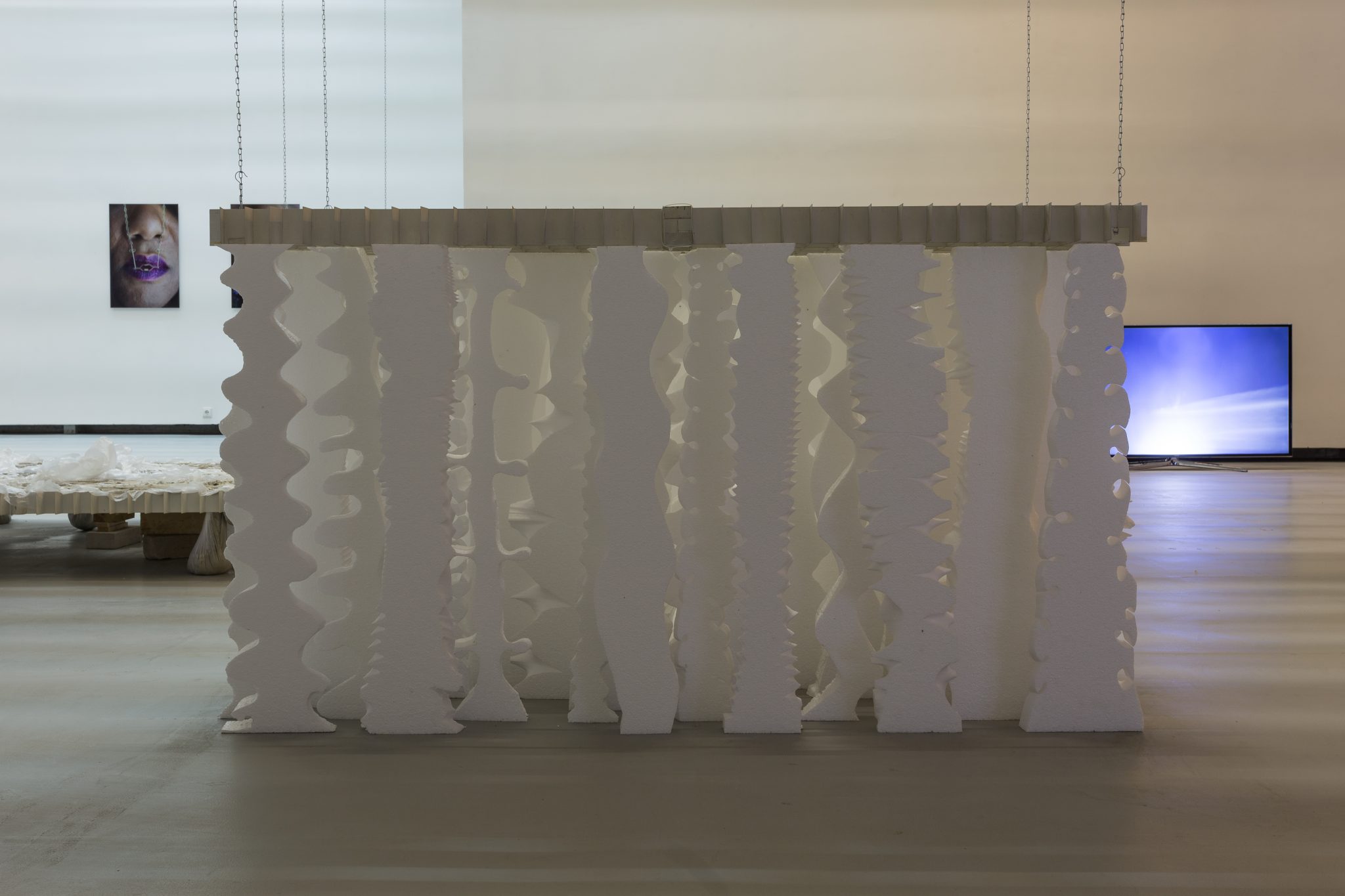

The exhibition “Futures” at the CAC aims to be a comment on Rothman’s article and his cinematic nostalgia, and to raise some purely speculative questions, including: Do our fears about (and desires for) the future age? And if so, how? By what process are these fears and desires transformed to construct the present and whose present is it? What makes us return to some of the fears and loves of the past, and what makes others of them irrelevant? How do outdated desires gain new, unfamiliar forms and turn anew into promises for the future? How do we go about categorising the world into the past and the future?

In the current flood of big-budget reboots, oriented towards nostalgia for yesterday’s future, the future might appear unchanging; they also imply that “we”, the spectators, have a common understanding of the present. As the word “retro” implies, some anticipation of the future has already aged. From this perspective, the popularity of retrofuturism, or the strive for it, can be viewed as a colonizing phenomenon (and one that, in my view, drained the newest season of The X-Files). It also invites us to think of the anticipation of the future, as well as the end of it, as globally shared, linear phenomena. But what if one’s subscription to the globally expansive market was delayed? Can we also speak of a critical retrofuturism? A retrofuturism that might awaken our sense of the present?

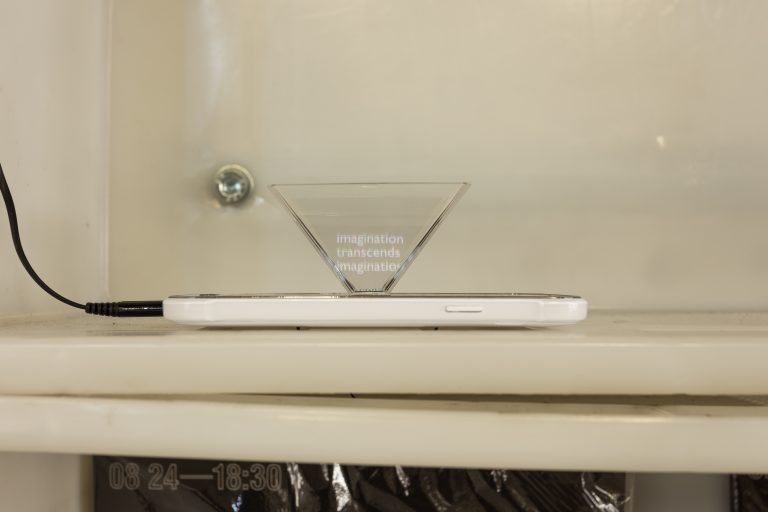

Hence, the choices of “Futures” echo Deleuze’s crystal – a type of time-image, the smallest unit of duration, which is visually expressed in cinema and which reveals a continuous interchange between the actual and the virtual: the presents, which pass, and the pasts, which are preserved and inform the present. As every actual is surrounded by the virtual, they are always informed by on and another, always in the flow, but they don’t collapse into each other. We see time in the crystal, which is why it can only become apparent in an allegory, such as a mirror and/or other workings of repetition, which show how we inhabit time.

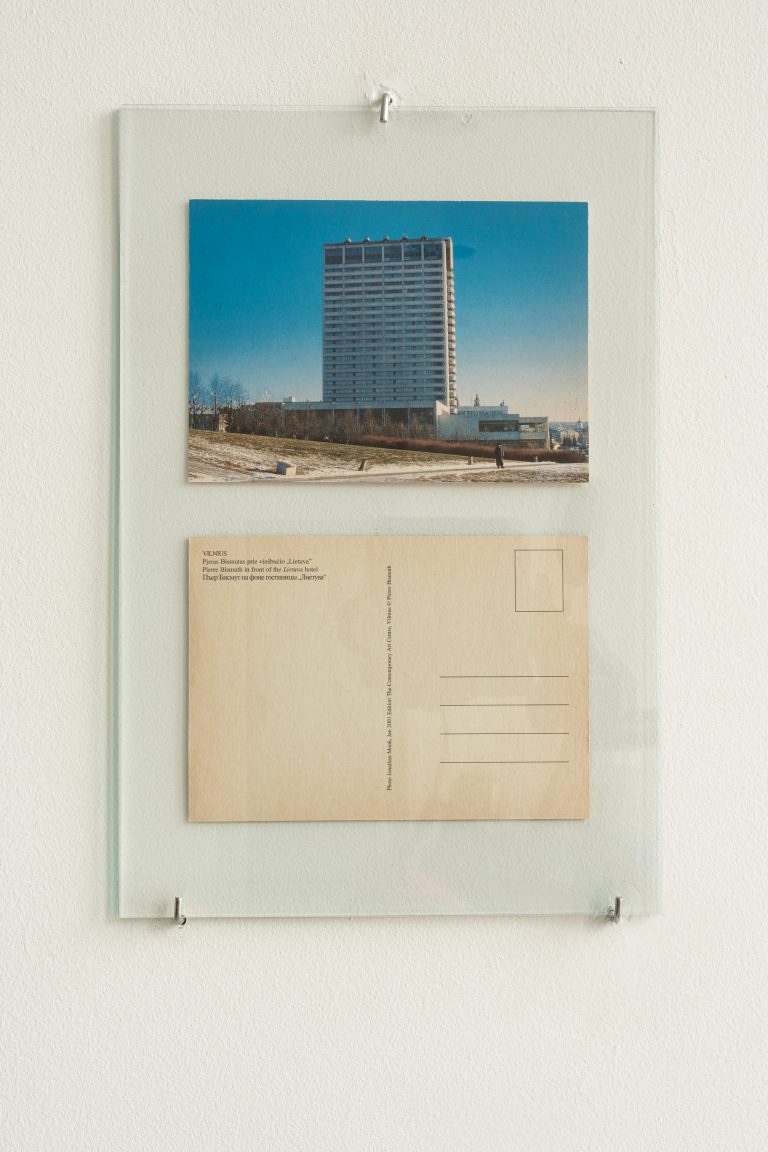

During the opening of “Futures”, the first seasons of The X-Files will be revisited in remembrance of their premiere in Lithuania, which marked the economic upheavals and our fascination with the then-unfamiliar future. It is an open invitation to remember a love for retro-futurism in this part of the world where “the future” itself was once postponed. But is there anywhere worth rushing to? Rothman’s ideas will be revisited while the works in the show will call categorization into question by reflecting the allure of continuation and of the retro-future, which, by intermingling with the present, produces unexpected discoveries.

*The tenth season of The X-Files was released in 2016, almost fifteen years after the last episode of the ninth season, which aired in 2002.

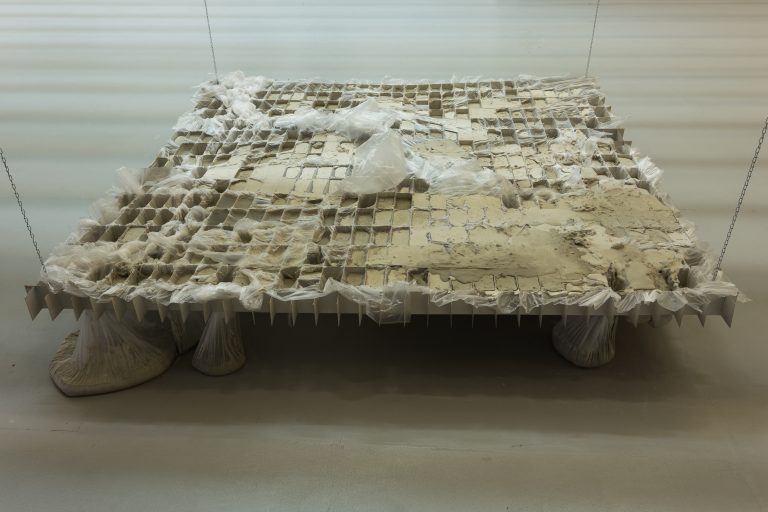

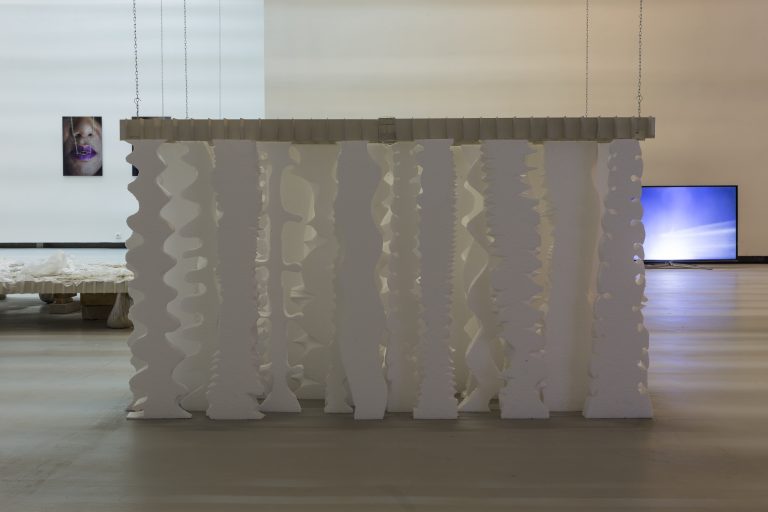

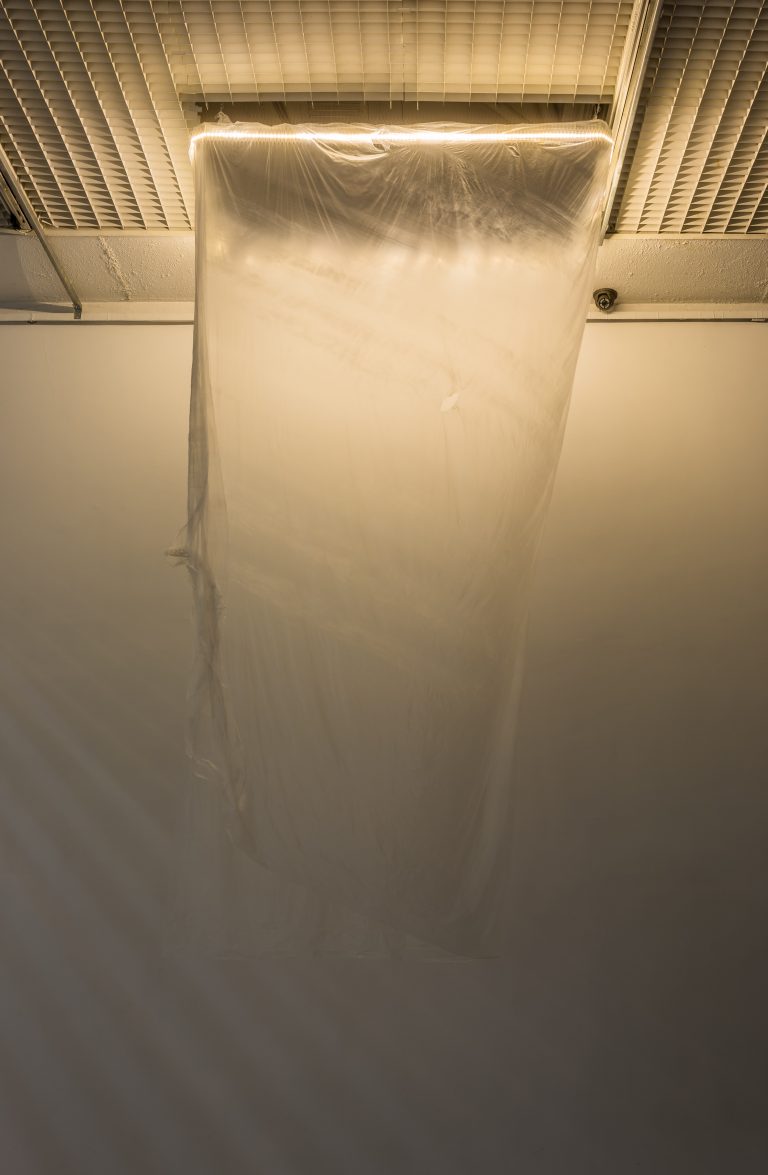

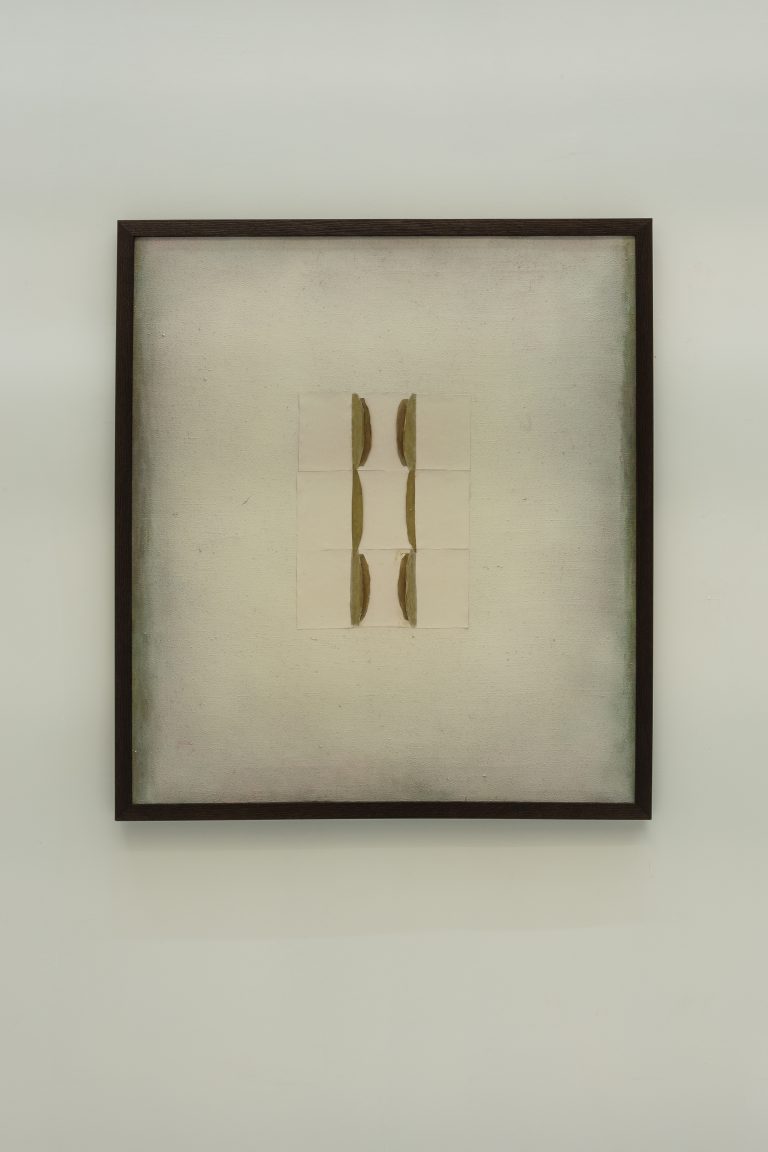

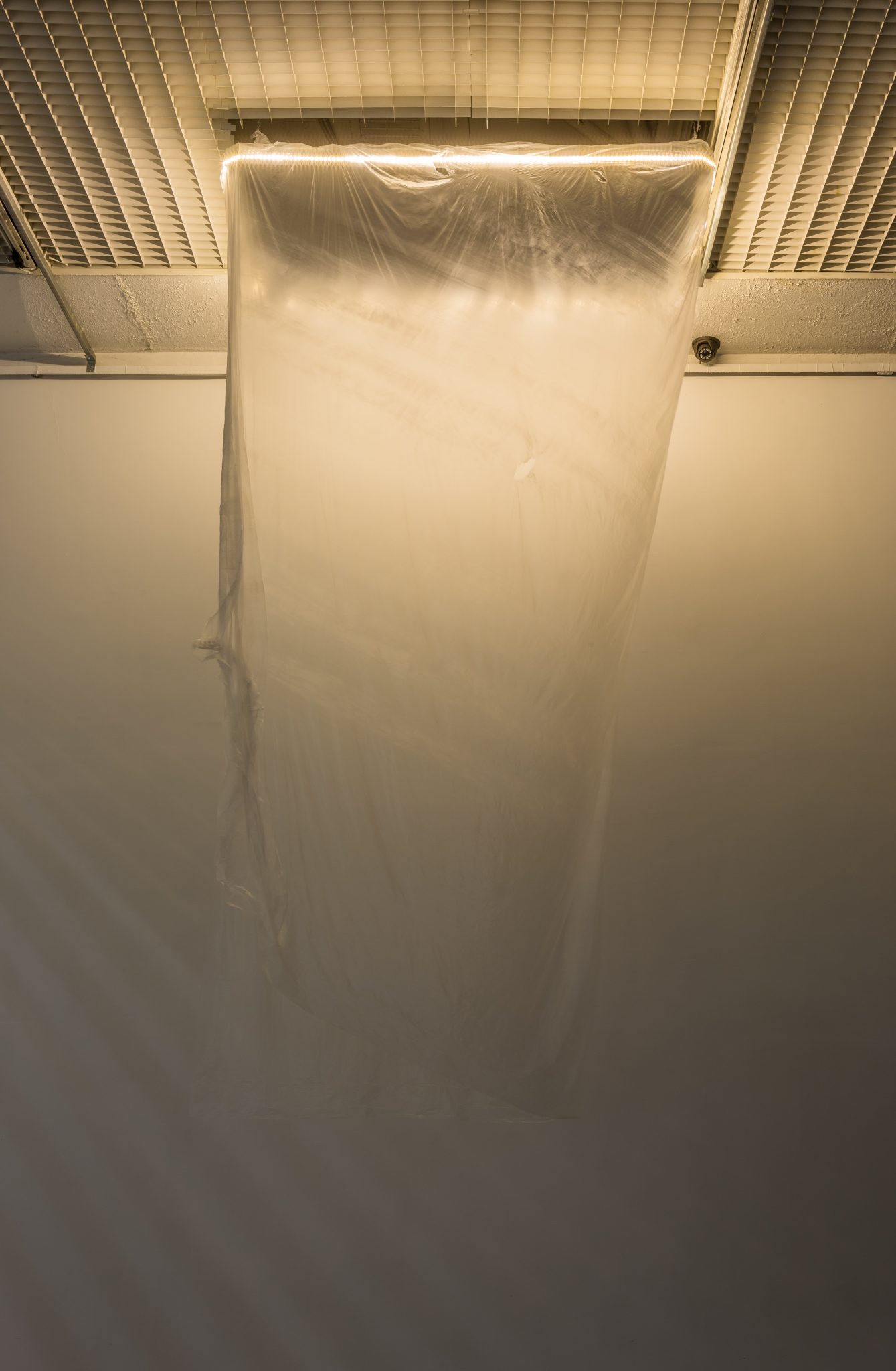

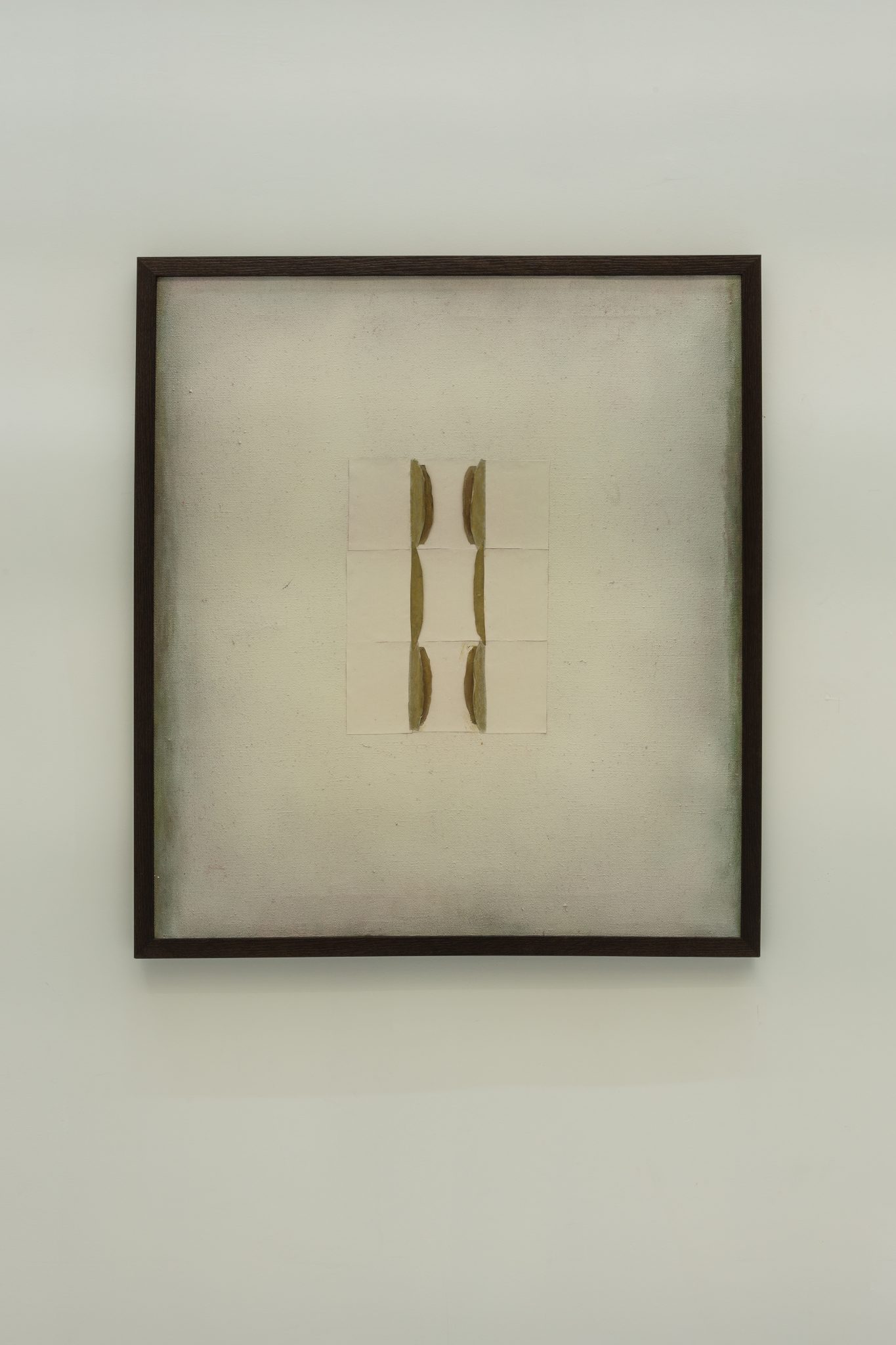

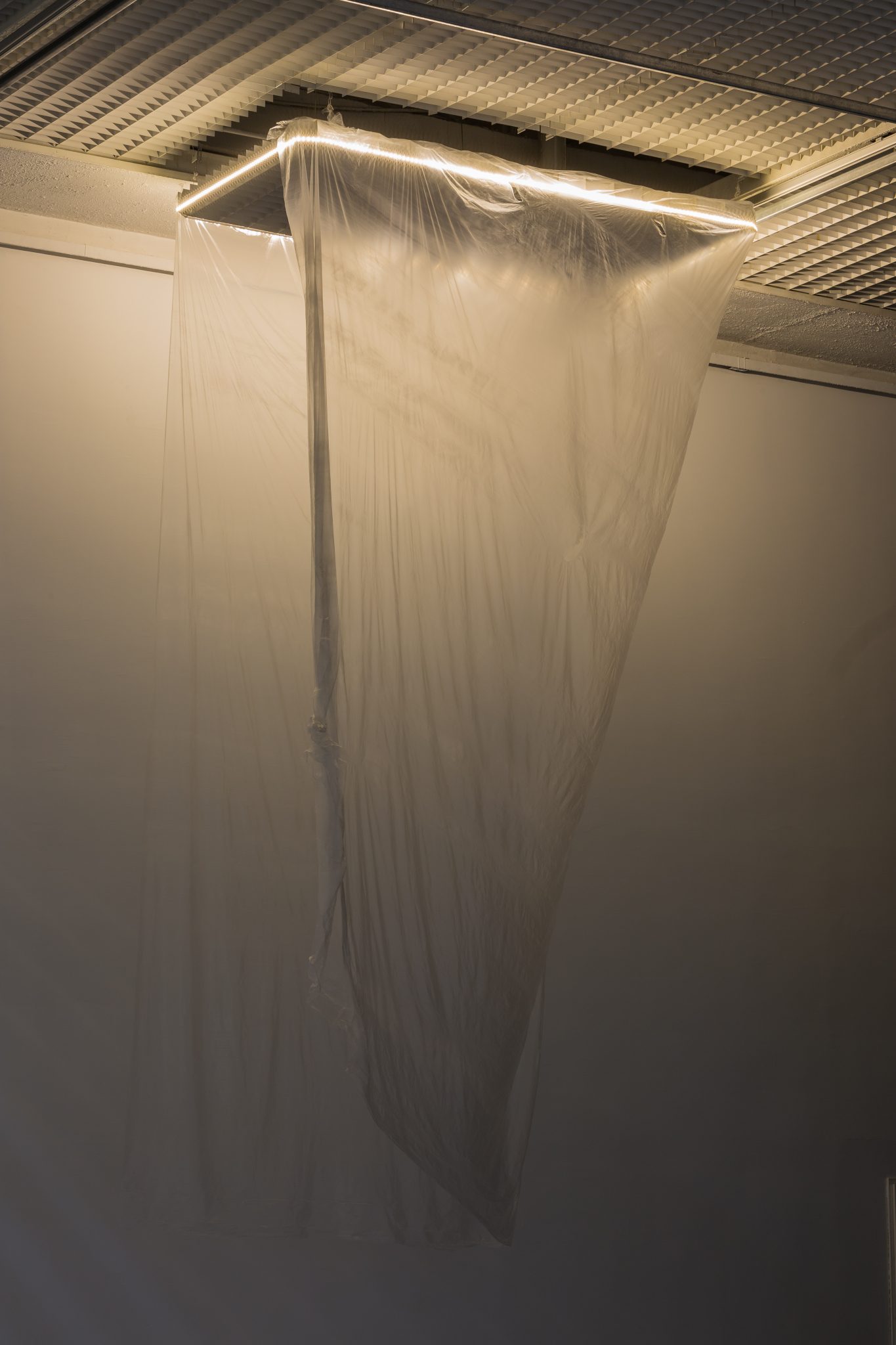

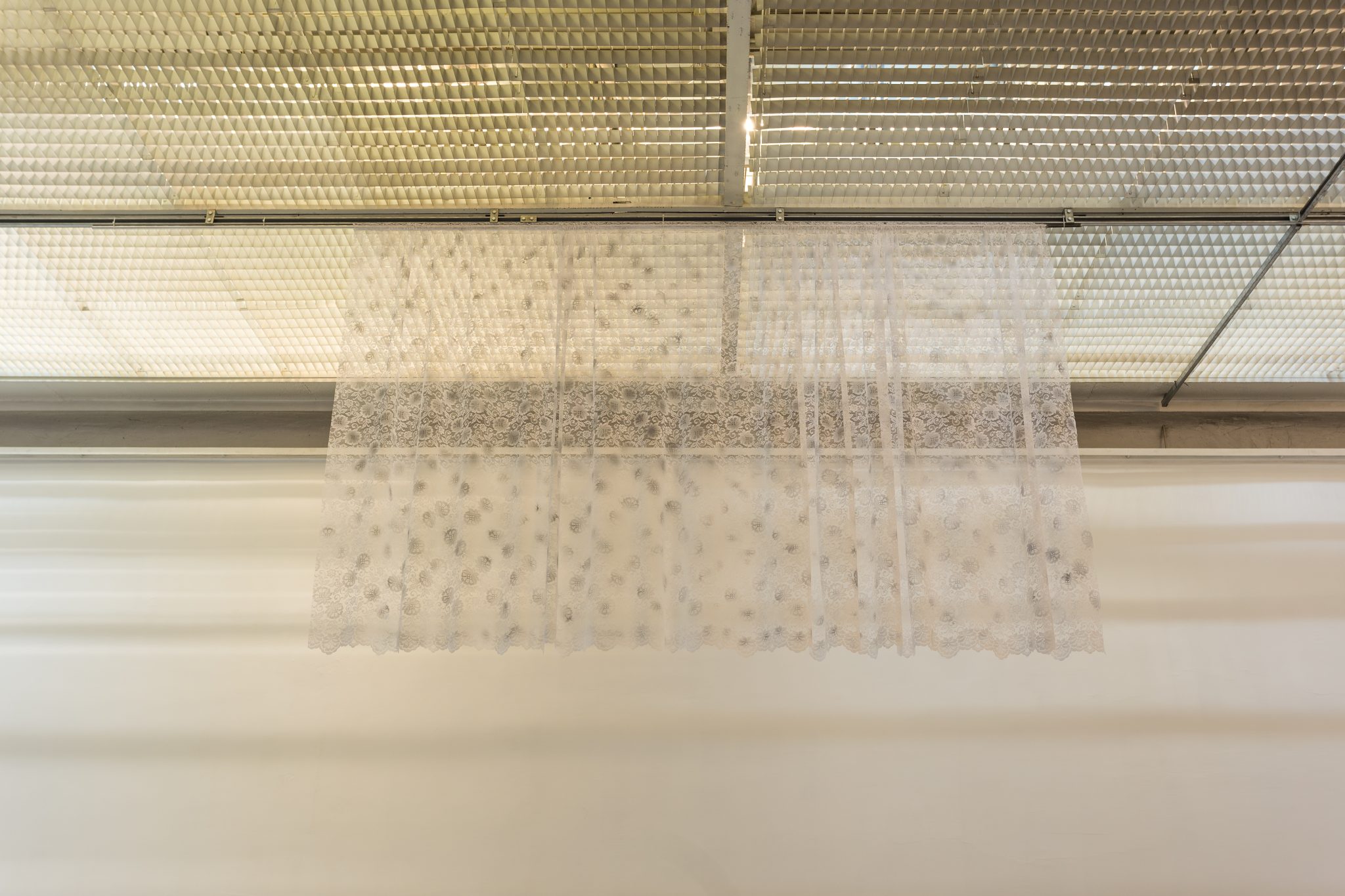

Image: Photograph of JL Dianthus by Tom T. Smit