Started in 2004, ‘Emission’ is a series of monographic exhibitions that introduces the most important Lithuanian artists, who during the previous decade have constituted a new language of contemporary Lithuanian art. These artists have received rich attention from the critics; they have participated in the important local contemporary art exhibitions and have represented Lithuania abroad on numerous occasions. Along with the activities of the Contemporary Art Centre, they have created a solid platform for the development of the new generations of artists. Audrius Novickas Passworks is the seventh exhibition in this nine artist series.

‘Passworks’ is being presented in parallel with the major international exhibition ‘Populism’ as Novickas‘ exploration of themes of national and political symbolism and the constitution of public and private identity is thematically linked to the main curatorial concepts of the Populism project.

Lithuanian artist Audrius Novickas presents three new works at the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius. Through two installations and a videowork Novickas examines the nature of connections between fragmentary, personal, cultural, social, and national identities; as well as the fragmented quality of the symbolic constructions used to represent them. Moreover, the works question the legitimacy of systems that create these identities.

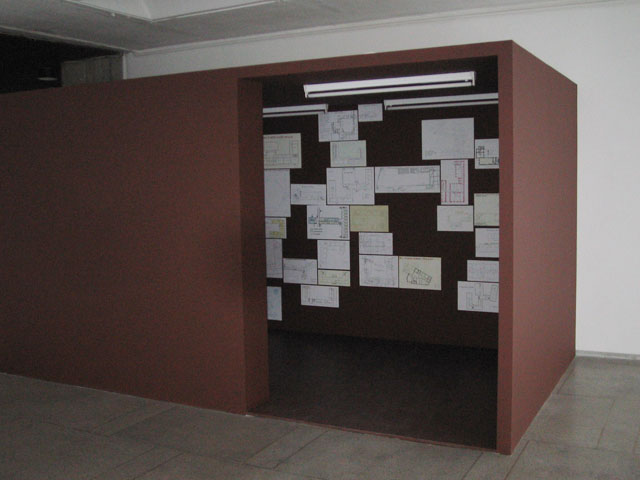

Total evacuation? 2005.

Emergency evacuation schemes of Lithuanian institutions for culture and education (about 120 items), tunnel 5,5 m long

This undertaking – to concentrate the emergency evacuation schemes of Lithuanian institutions for culture and education in one intimate space – was driven by different impulses. I was inspired by the architectonics of the schemes and by their references to labyrinths. Their functionality and efficiency-induced hesitations; the diversity of these strictly regulated bureaucratic documents, reflecting the inner cultural variance of the different institutions amazed me; as did a constant encounter with the marginal position of cultural and educational institutions in the ‘real‘ value system of contemporary Lithuanian society which led me to contemplation.

The five-meter long passage framed by emergency evacuation schemes of Lithuanian institutions for culture and education is not meant to express an apocalyptic dream. It is an environment which is physically tight, however it‘s open to contemplation, reflecting important features of human nature, and is suitable for raising a whole range of questions: where is the beginning [entrance] and the end [exit] of a tunnel? Is it really possible to access a tunnel and to leave it? Is it possible to forget the reason to leave while searching for an exit? Is something going to change after I leave? Is a total evacuation possible and what would it mean as an artwork, a radical protest, an illusion, a self-destruction, a realised utopia, or a possibility for a new beginning?

Tricolour sets. 2005. 10 flags (of Benin, Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea, Lithuania, Mali, Senegal).

Measurements – variable, total installation space – 450 x 170 x 285 cm.

This installation consists of 10 flags of different sizes. They have their prototypes – national flags of some countries of the world that have their flags composed of three particular colours – yellow, green and red. The three colours in all the flags of the installation are of the same shades, which do not necessarily correspond to the specific colours, characteristic of the authentic national symbols of Benin, Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Ethiopia, Guinea, Lithuania, Mali, and Senegal. In this case, the flags are neither ready-mades, nor naturalistic artifacts, but representations or versions of the standardized tricolour code. The code, which emerged as a symbolic message at a certain historic time in concrete sociocultural space, was later recreated and used in other temporal and spatial contexts.

Bolivia was the first country to decide to make the red-yellow-green tricolour a national symbol in 1888. Lithuania was third to officially announce the tricolour for its national flag in 1918 and remains the only country in Europe with this schema. The second country to raise a green-yellow-red flag in 1898 was Ethiopia. As the only African country which managed to avoid colonisation, Ethiopia became a model and a source of inspiration for those African countries that achieved liberation and were searching for their own national symbols during the 1950s and 1980s. As an outcome of that process, the combination of the yellow, green and red started to be considered Pan-African Colors.

Tricolour Sets is composed by fastening the flags one-after-another in the specific chronological order in which the flags were legitimated. Each flag is proportionally larger than the previous. With this exponentially expanding sequence the artist accentuates not only the resonance of elements in space but also the increasing concentration and deliberate spread of representations of this symbolic code in the world. Namely this paradoxical purposefulness raise questions in relation to the Lithuanian tricolour as our national symbol and the formation of our identity. Is there any rational explanation for the Lithuanian choice of the colours which by the time they were selected had already been used by Bolivia and Ethiopia, and have since spread to a number of African countries? Is it important that all three countries which adopted the tricolour first (Bolivia, Ethiopia and Lithuania) are Christian? How in this context should we approach considerations of the Lithuanian inter-war geopolitic Kazimieras Pakstas who proposed that Lithuania needed to move to Africa? How may the uniqueness of our flag be viewed in a European context: as a challenge, as an evidence of our uniqueness or as a misunderstanding?

ID. 2004. DVD 5 min.

This five-minute video is a type of performance documentation. It elaborates on the efforts of an individual – a representative of a postmodern culture in which traditional blood-ties are broken and ethnic symbols have become consumer signs – to find an inner balance and fit the fragments of their ethnic identity into a collage-like whole. The reading of this work requires knowledge that the artist is the child of a Caraite man and a Lithuanian woman. Further, it‘s bounded by the fact that he has been formed by an environment dominated by Lithuanian culture, and has only recently started to intensely follow Caraite culture and the life of the Caraite ethnic community. The artist‘s efforts to reveal a previously dormant part of his identity is limited by the fact that Caraite language and religion – the two most important elements of ethnic definition – aren‘t yet easily recognisable to him. Therefore, he is unable to authentically relate to this culture. This makes his approach hardly different from the tourists and pleasure-seekers who visit Trakai and see the community centre of Caraites in consumer oriented signs such as ‘Kibinai’ (a meat pie, very popular in Lithuania that is a Caraite speciality), ‘Caraites’, ‘The Trakai Castle’, ‘Vytautas the Great’ (a Grand Duke of Lithuania in the 14th century who made Lithuania one of the largest countries of Europe and invited Crimean Caraits to Lithuania) and ‘The Old Capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’. Thus, it is only through easily identifiable consumerist symbols that the author can speak about his fragmentary encounters with the authentic Caraite culture in a way that can be understood.