I’ve never seen the skeleton of a dragon. Nor even the real bones of a dinosaur. Though I remember well my visits to the Natural History Museum in London five years ago. That majestic building of Roman architecture is itself reminiscent of an unknown skeleton. There, in the European capital of taxonomy, I saw Dippy for the first time. It was difficult not to notice the biggest exhibit in the museum – the copy of diplodocus’s skeleton, assembled from 292 pieces of cast bone. But somehow it almost merged with the organic moulding of the building’s walls. Being an imitation himself, Dippy mimicked the mouldings and at the same time mocked them. For more than one hundred years this gigantic alien body occupied 21 metres of the museum’s central exhibition space until in 2017 the procedure of moving him to the dinosaur archive began. Before leaving the limelight, the rock star of fossils is on tour across Great Britain, so that everyone can see him one last time. The production of Dippy, as well as six other copies of the dinosaur’s skeleton, was financed by the wealthy American of Scottish origins Andrew Carnegie. He called himself a “diplomat of Dinosaurs” and believed that in the presence of such a pre-historical creature any cultural differences of nations become insignificant. In total there were seven museums in Europe and South America that received Carnegie’s gifts.

In the second hand store, Humana, as well as in the Natural History Museum, there are plenty of different things, sorted according to a clear system of classification. Arranged in different colours, disinfected with the same ethanol, things are ready to return to the market. Here the curators of exhibits are the shop assistants, and the assortment is supplemented everyday, to entice you back again and again. Yesterday I found quite a cool, but much too small, pair of Acne Studios jeans, a real ground-reaching fur-coat of nutria, a hand-sewn dark blue dress and six extremely warm sweaters made from Irish wool. In Humana sweaters become sweaters again and trousers return to being trousers. All of this is in contrast to the pedestrian streets of big cities where the distribution of brands is very clear, and the same combinations of shops appear repeatedly. You could be in London, Paris or Copenhagen – the same high-end boutiques will be side by side in one area and the high street stores on another avenue. Meanwhile, you can only guess where the items in the second-hand shop have come from: maybe they were worn down, did not fit, someone became fat or skinny, died. You may even wonder how many times this item has ended up in a second hand shop? Sometimes you get the feeling that there is clear evidence of a passing trend, but equally, it is possible that the entire collection of plaid shirts is from the same person’s closet and ended up in your local Humana by accident.

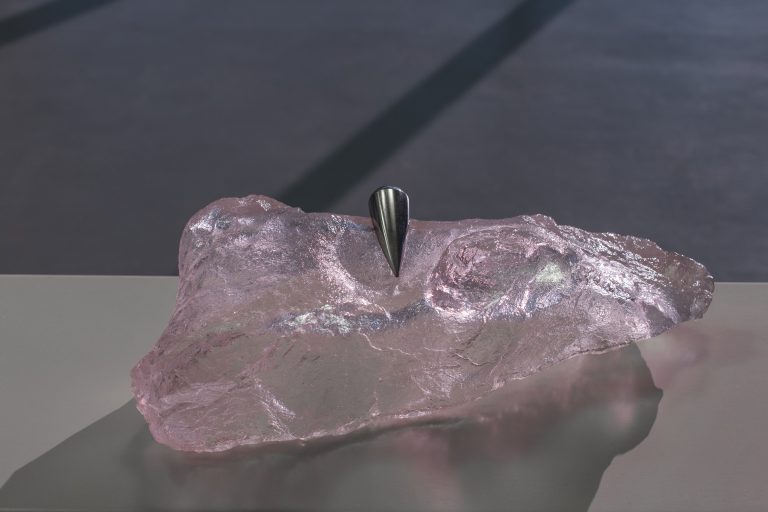

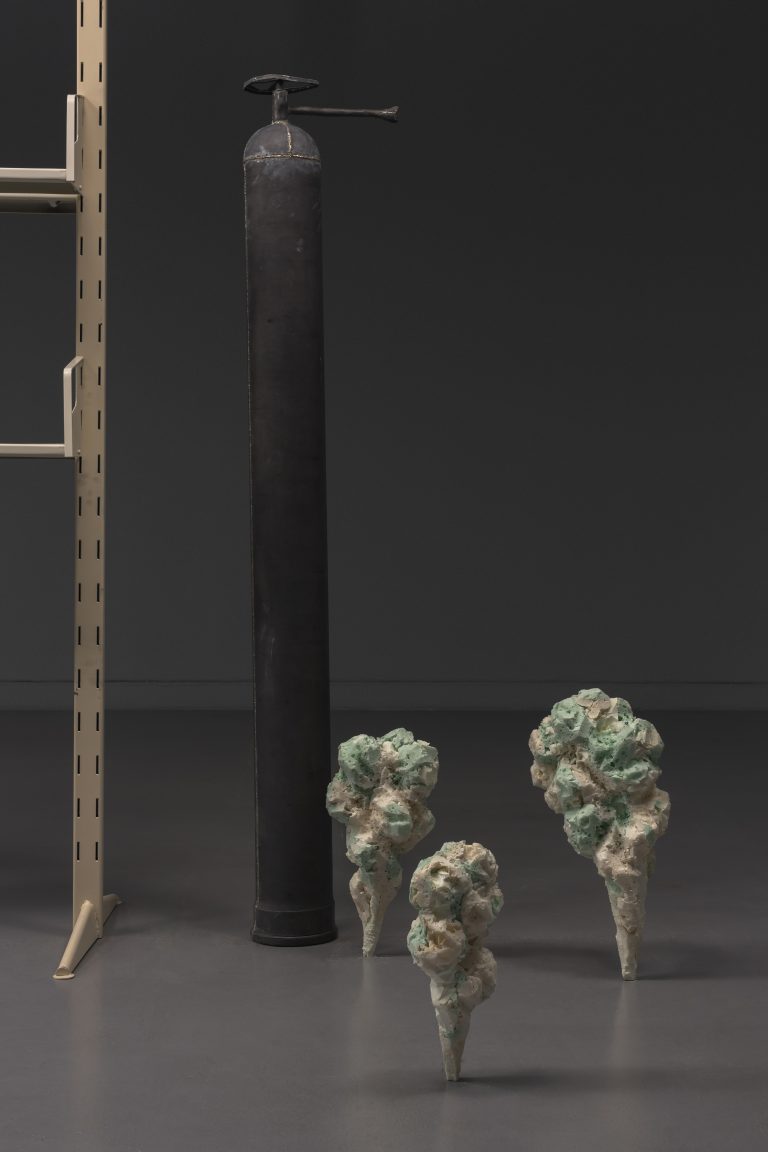

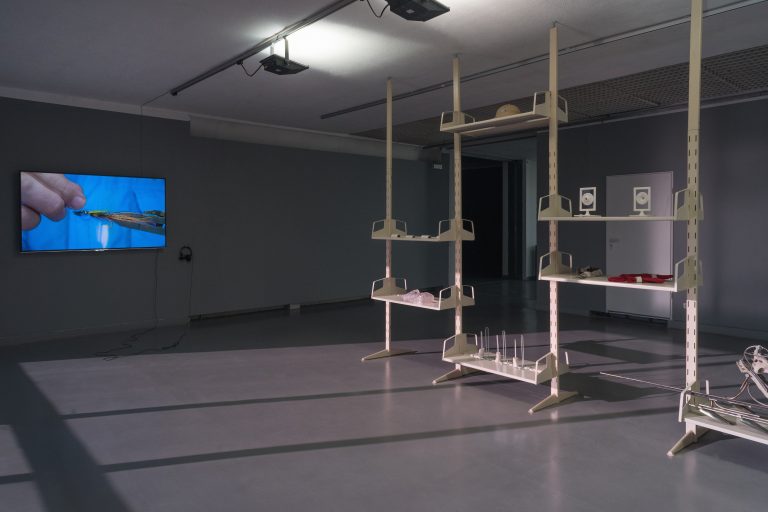

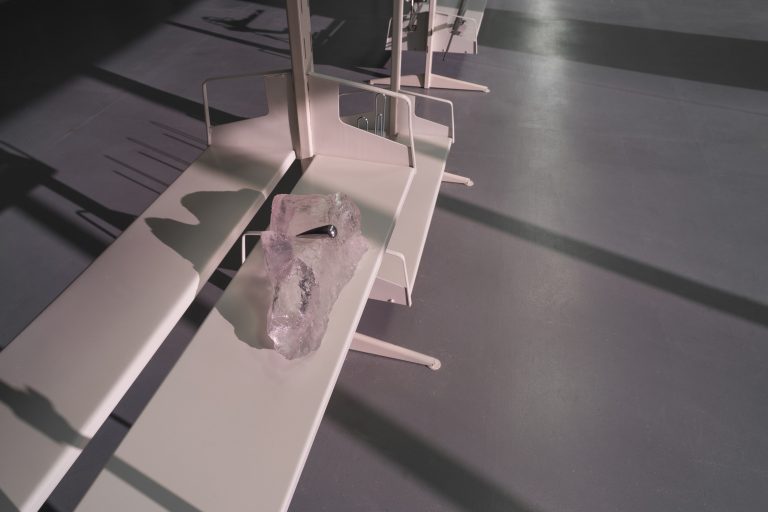

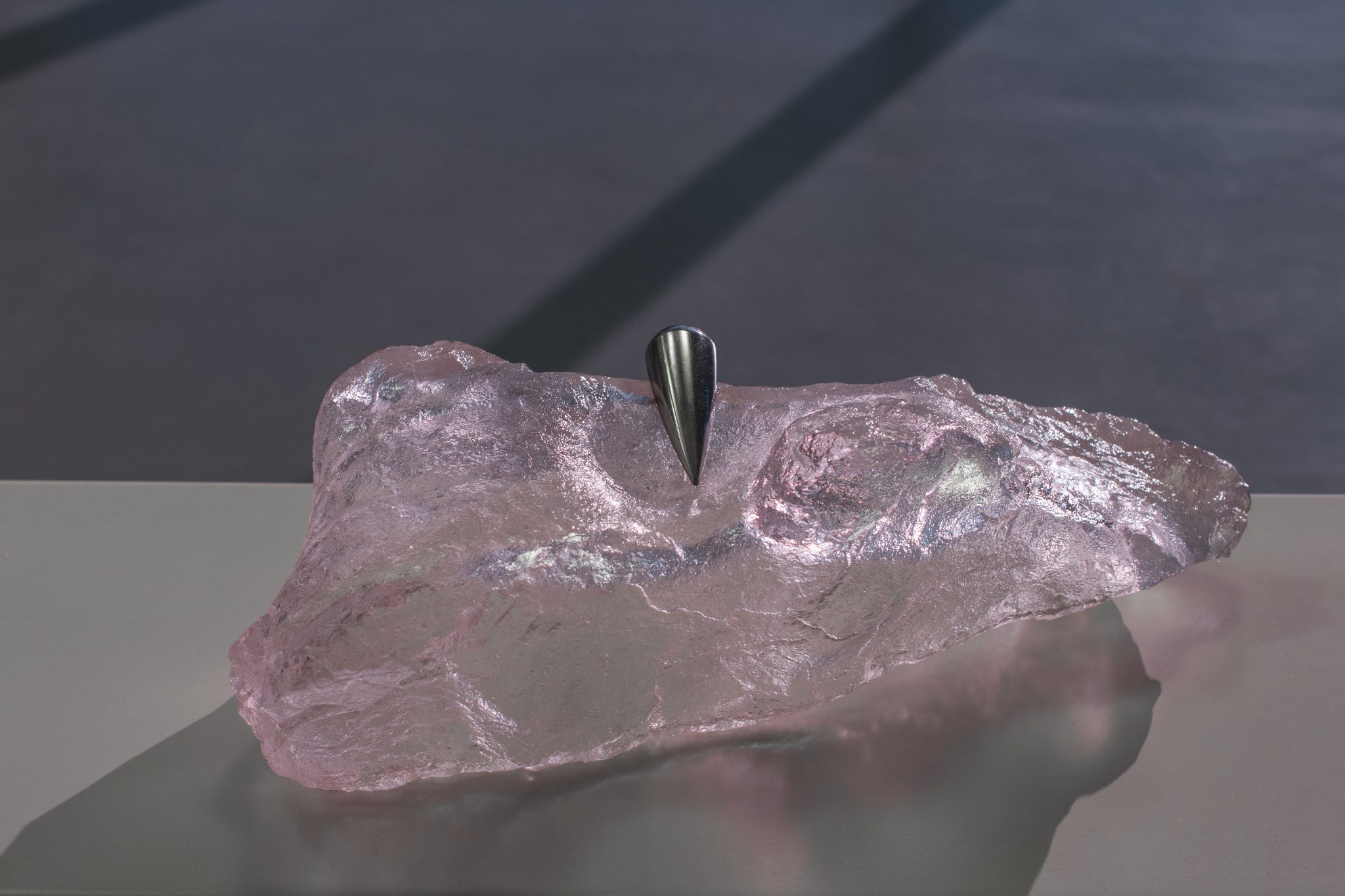

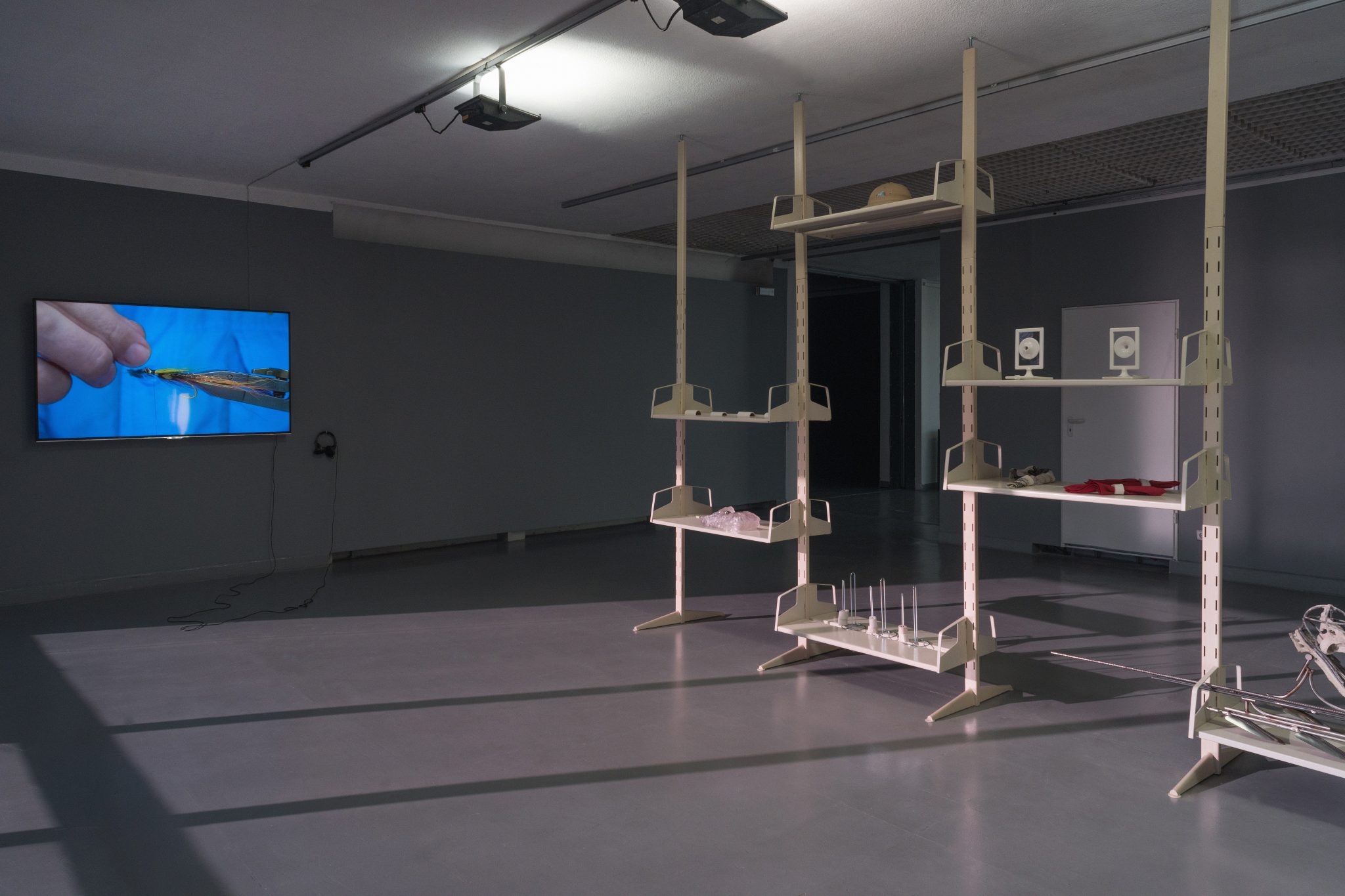

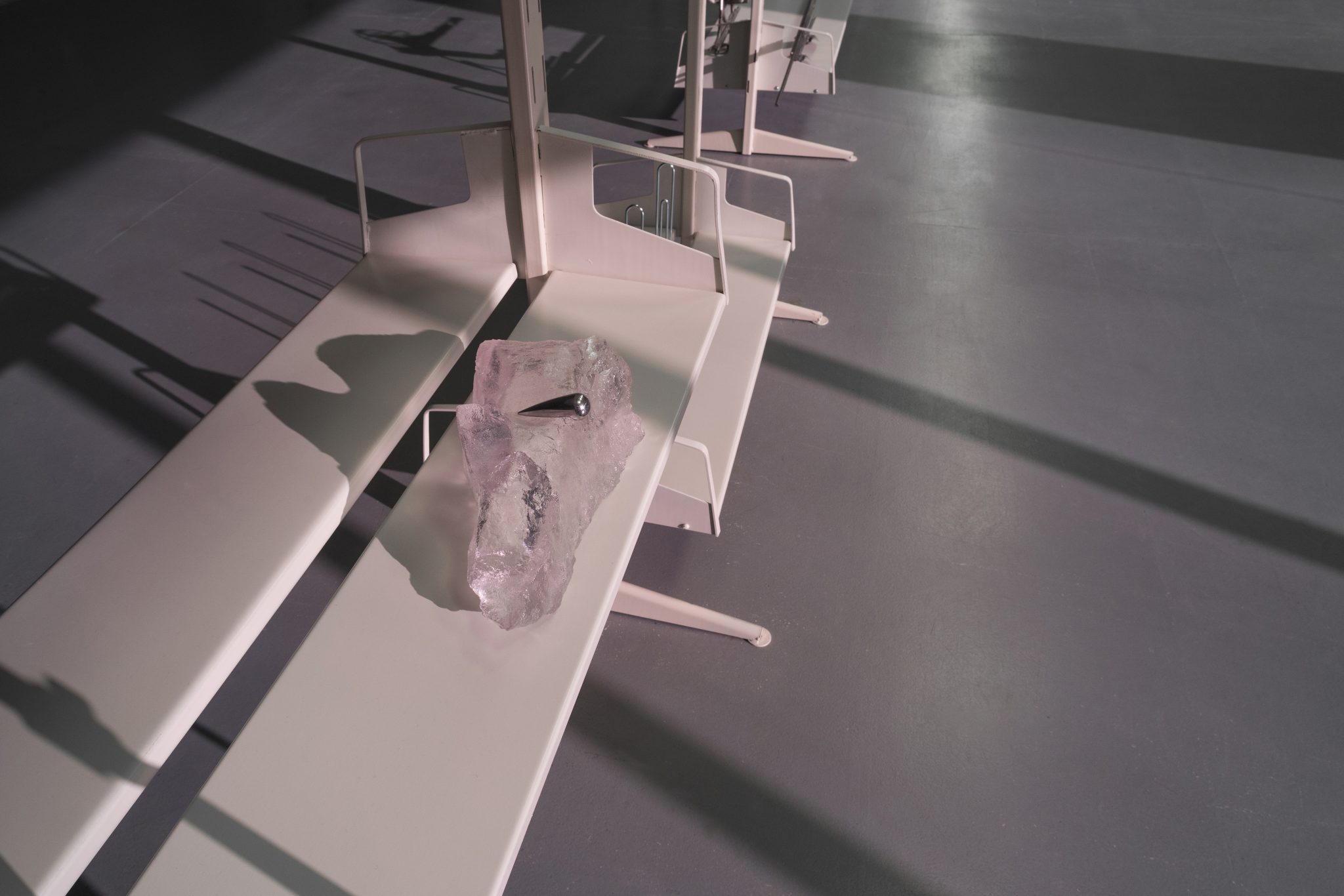

A group show is another meeting point of things that have not necessarily had anything in common before. Coming from similar corridors in different countries, the collection of artworks in the exhibition “Tail and Heads” could seem to be the result of a hunt for the tendencies of young European contemporary art. But the only feature that connects all of the artworks is a desire to escape that sieve of taxonomy – to shine like a coin, thrown by politicians who got the exact same number of votes. Two sides of one coin in this case, are not only heads or tails, but also the strange spine of an unseen animal between them. The artists in this exhibition believe, that if you look carefully enough, you might catch it. They bring home a carp from a grocery store, cut its belly and expect to find another fish inside.

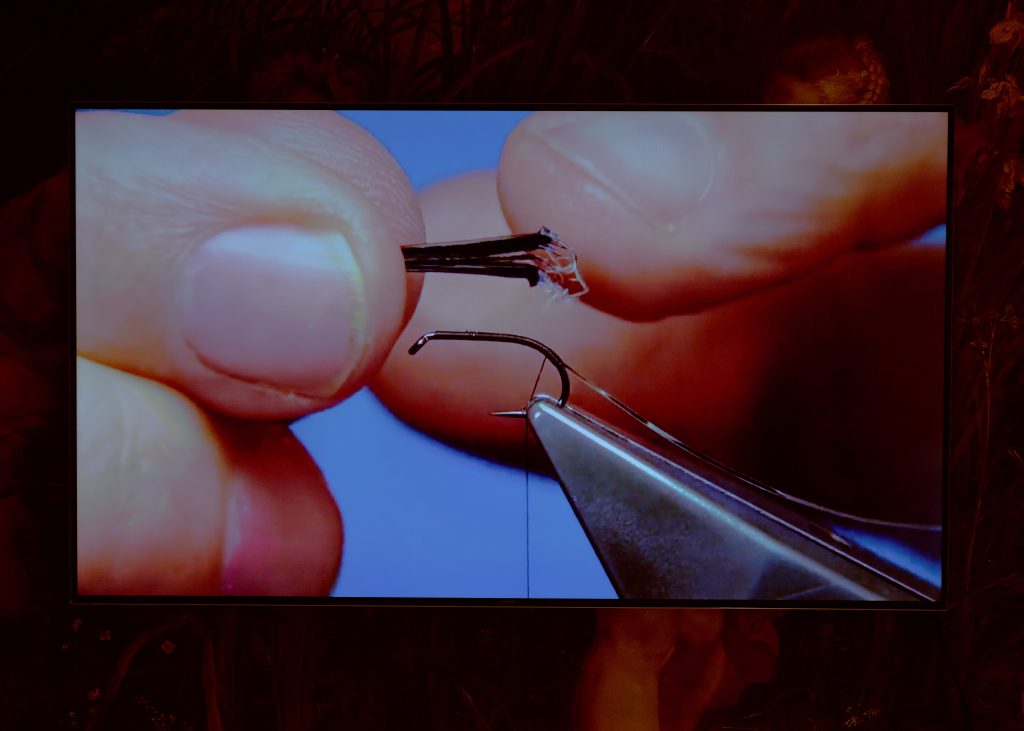

Image: still from John Ryaner film The Taxonomy of Imitation (2018)