The exhibition will be opened on December 21st, Friday, 6 p.m., with Professor Rita Šerpytytė’s lecture “Nihilism and the Return of Reality”.

Audit is a professional system of inspection of accounts formed in the 18th–19th centuries. In 1840 the majority of railway construction companies in Great Britain were required to register the number of rails in a general system and to build a safe method of revenue accounting, thus creating the conditions for professional audit. Since the 19th century audit is understood as a rational system of assessment that can establish not only what is present, but also what is absent or lacking. In this respect audit operates not only in the system of inspection of accounts, but also in various other processes of naming and recognition of reality, and establishing the right to any kind of existence.

Participants:

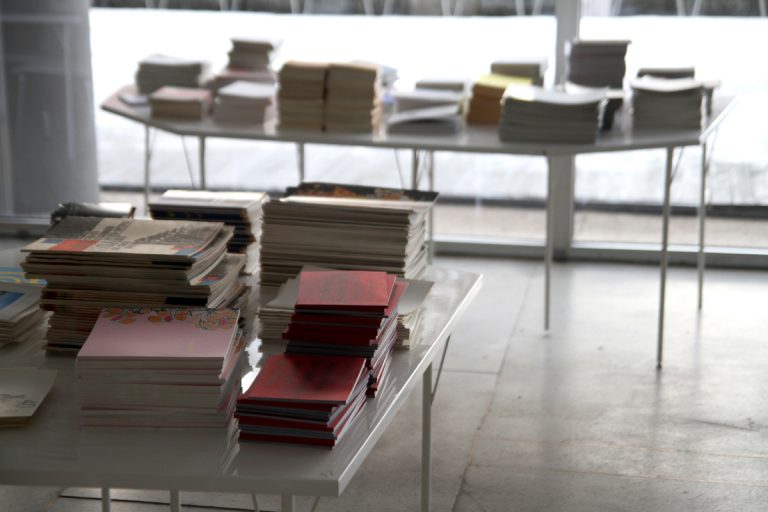

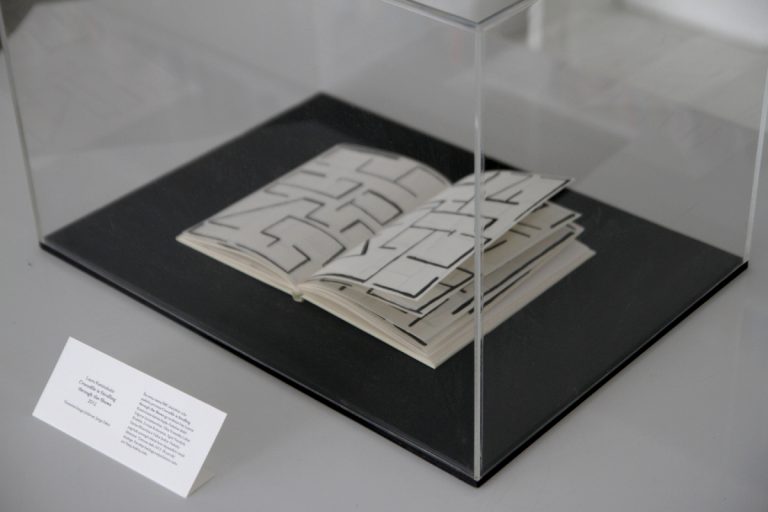

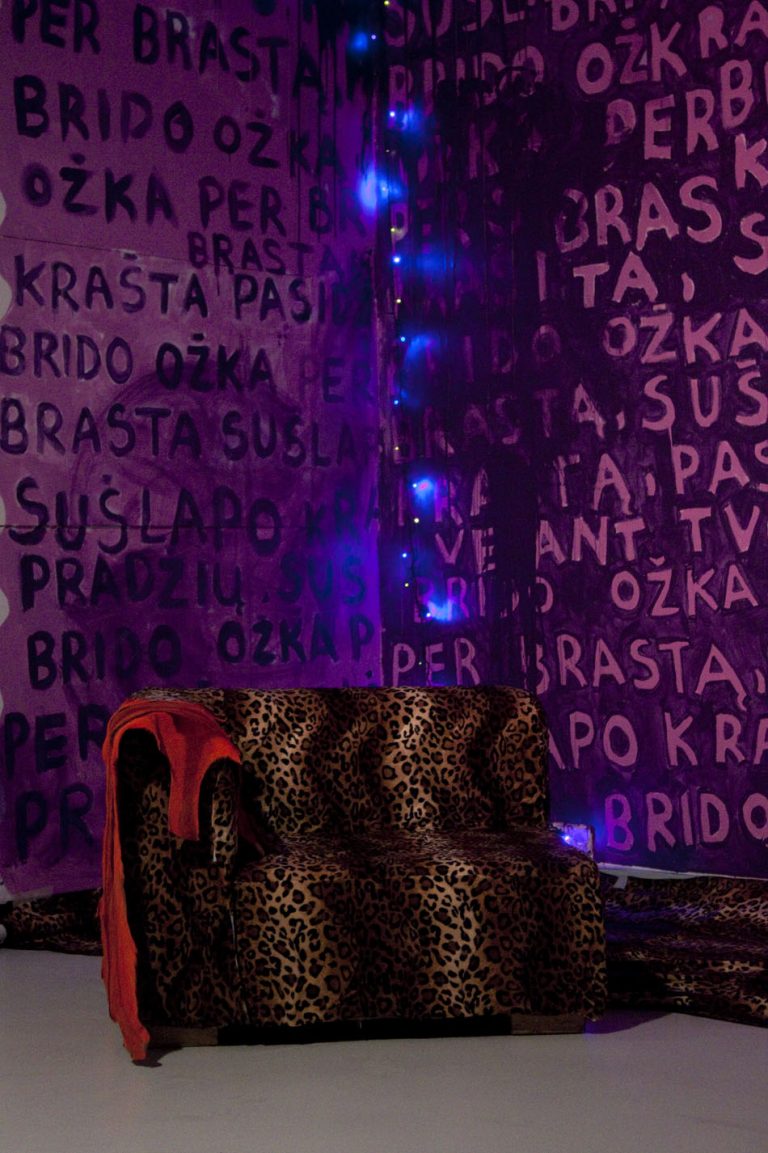

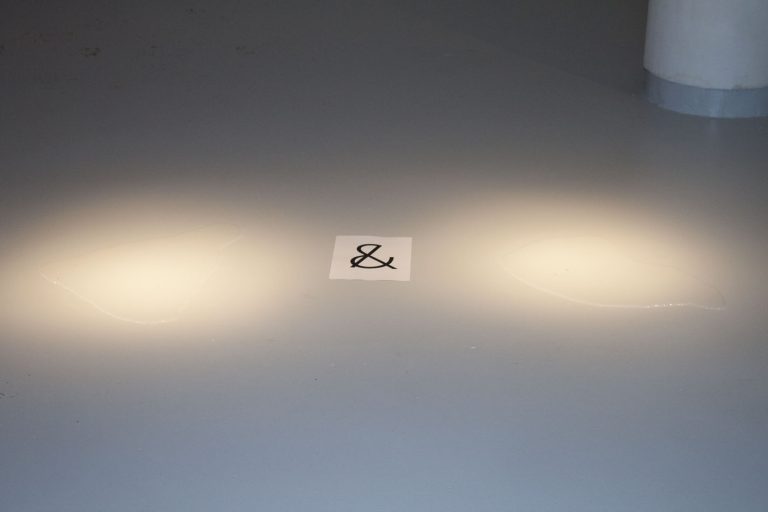

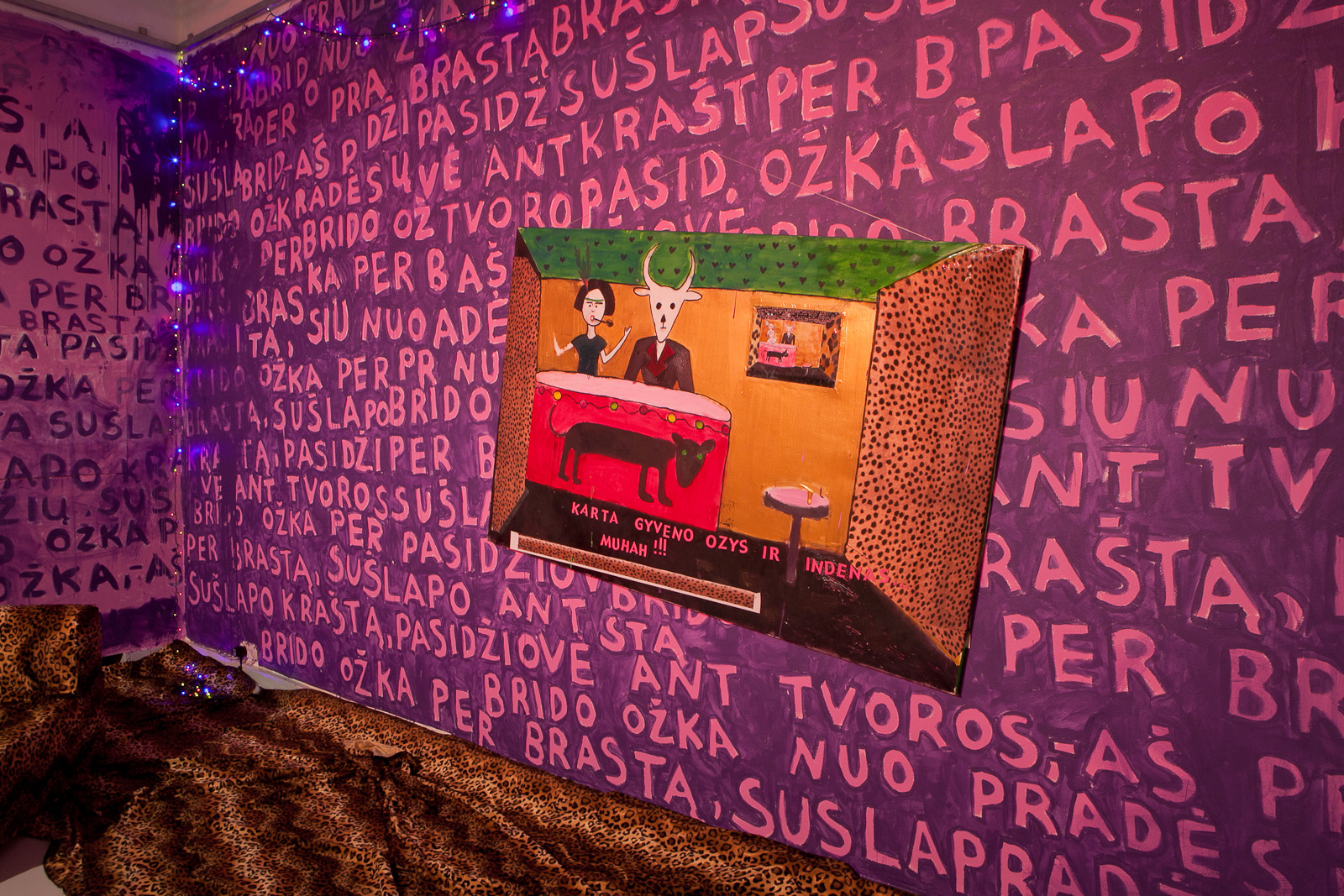

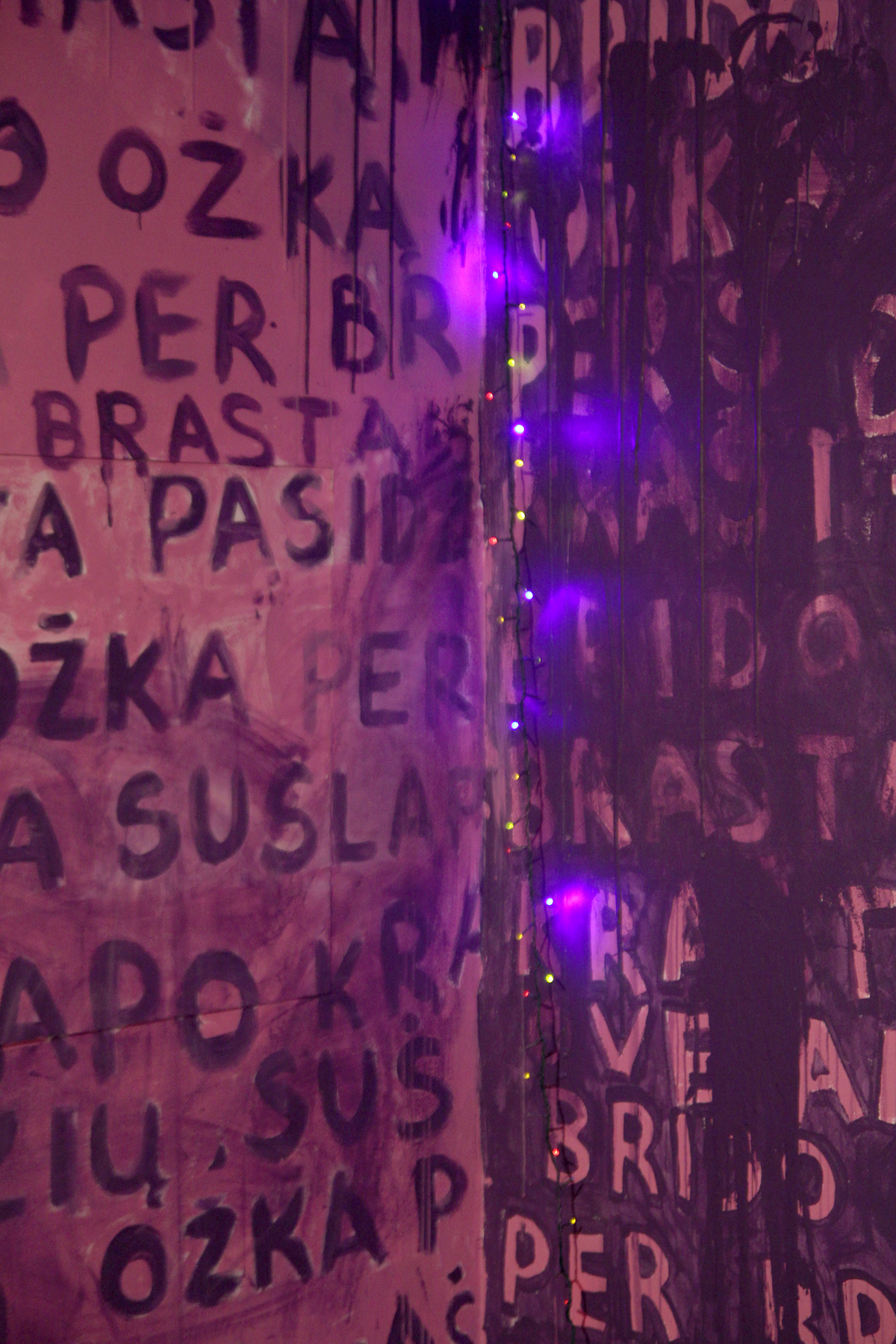

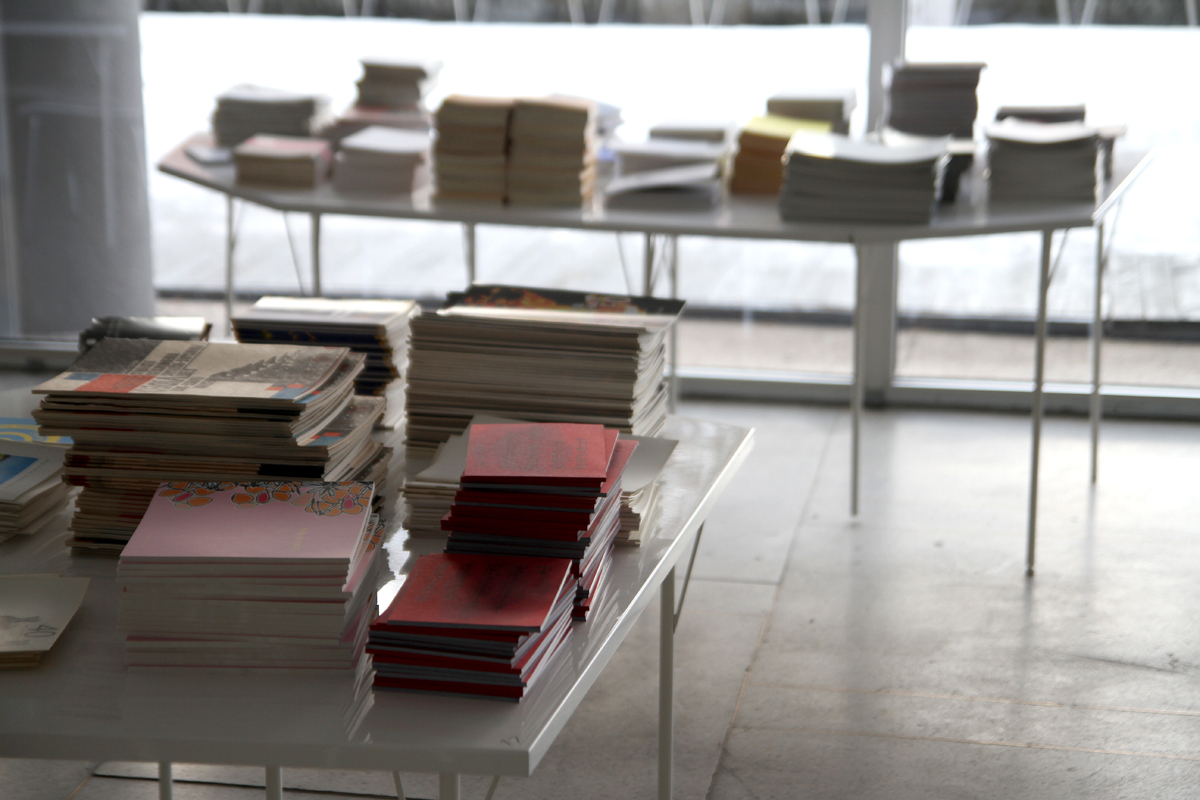

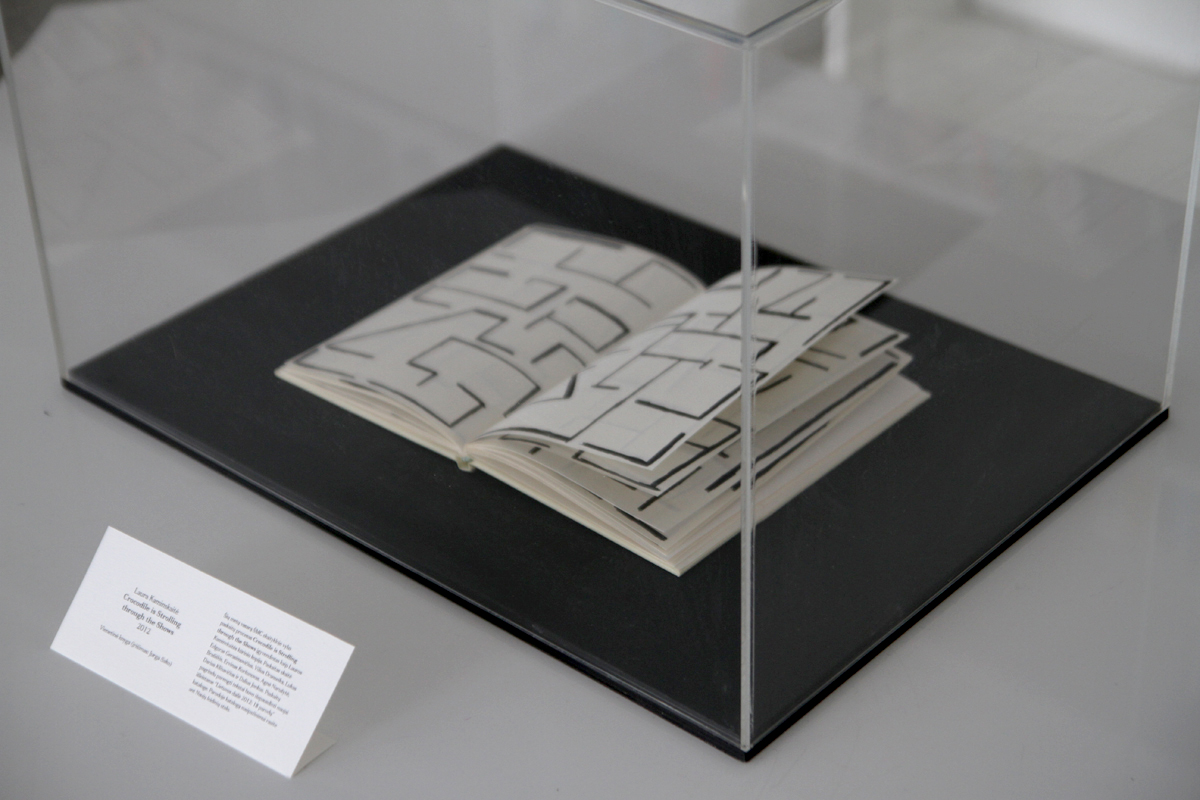

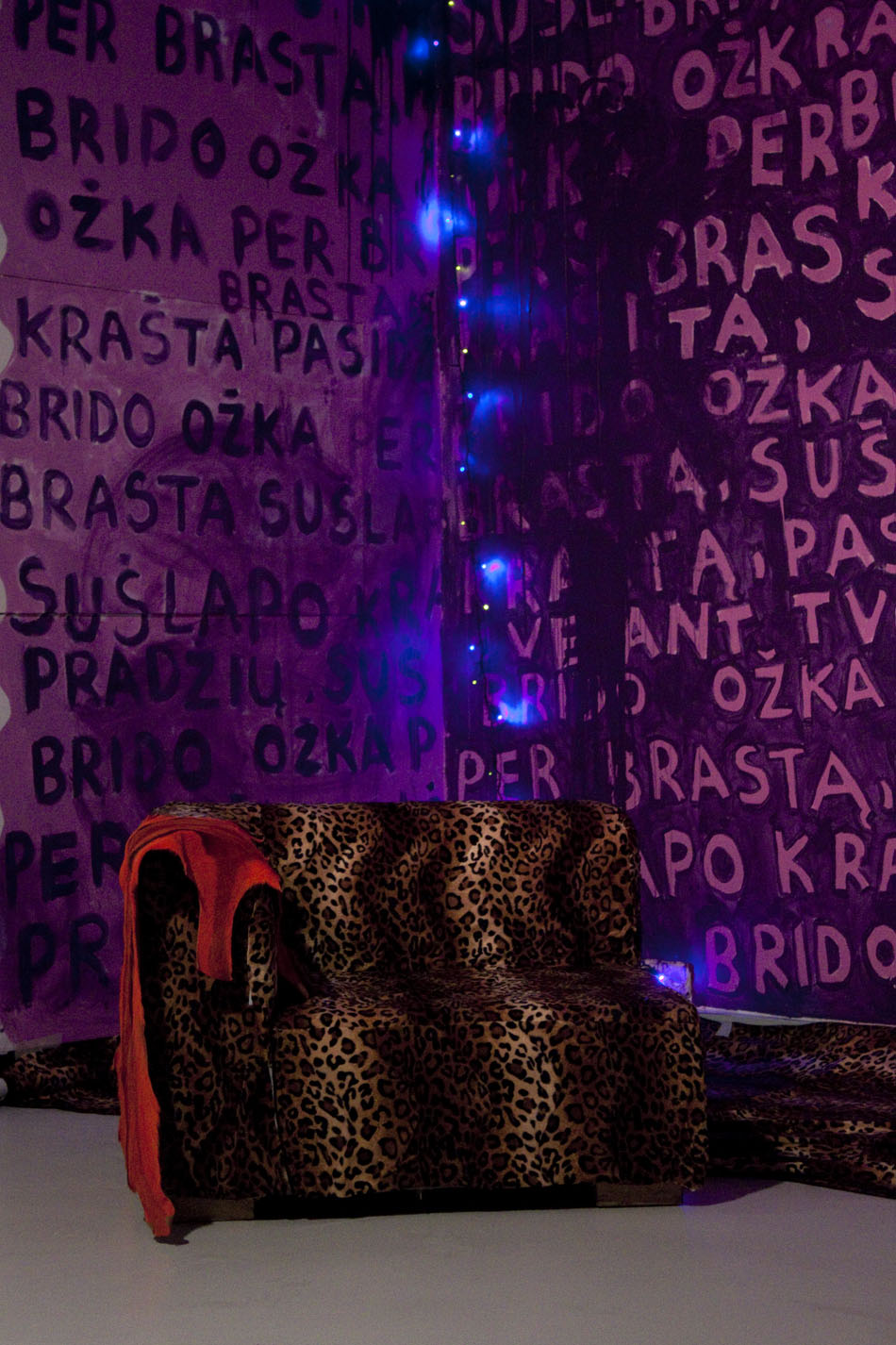

Antanas Gerlikas, Liudvikas Buklys, Laura Kaminskaitė, Naglis Kristijonas Zakaras, Elena Narbutaitė, Rimgailė Dručiūnaitė, Vytenis Burokas, Monika Dirsytė, Darius Mikšys, Rita Šerpytytė, Jonas Žakaitis and Aurimė Aleksandravičiūtė, Federal #3, MoMA Millennium Magazines, newly published catalogue “Lithuanian Art 2012: 18 Exhibitions”, and free CAC books.

Curator:

Auridas Gajauskas

Cover Letter: Audit

On 1 March 1789 Olaudah Equiano, better known as Gustavus Vassa, the African, arrived at the London County Hall, where he registered his newly published autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. On the back cover of the book Vassa indicated twelve official book dealers, but decided to leave out the printer, most probably the fairly well known British poet Thomas Wilkins.

The 18th century Royal Navy muster rolls analyzed by Vincent Carretta in 2005 revealed that the facts of birth indicated in Vassa’s autobiography did not correspond to the truth. Carretta asserts that Equiano was born in 1747 on one of the plantations in South Carolina, while according to Vassa’s account his life began in 1745 in the Igbo tribe, South West Nigeria. Regardless of the fact if Equiano was born in Africa or America, when he was bought for forty pounds by the British Royal Navy lieutenant Michael Henry Pascal on the island of Barbados in 1756, nobody on the slave ship African called him Equiano, but addressed him by the name of Jacob or Michael. In the autumn of 1756 the trade ship Industrious Bee led by Pascal left the Caribbean for England. In addition to tobacco, cinnamon and other goods, the ship carried Equiano, or Michael, as a gift to Pascal’s relatives in London. Pascal soon renamed him in honour of the Swedish king of the 16th century Gustav Vasa. During the trip Vassa began to learn to read. Taking an example from Pascal and other white men, who were in the habit of reading aloud, Vassa tried to speak with books. He would say something and, having put his ear to the book, would listen what the voice on the other side of the cover or page had to say in response. In February 1759 Vassa’s guardian Madam Guerin, in whose house he stayed when he did not accompany his rightful master, agreed to baptize him and on this occasion gave him the book Essay Towards an Instruction for the Indians by Thomas Wilson.

Bishop of the Anglican Church Thomas Wilson, known in the 18th century as the administrator of the Diocese of Sodor and Man scattered on the islands between Ireland and England, wrote the book, which is sometimes referred to as Guide to the Indians, in 1740. He was most probably prompted to write it by his meetings with representatives of the Cherokee tribe, who had been brought to London by the founder of the Georgia colony, general James Oglethorpe, in 1735. The book consists of fifteen conversations between an Indian and a missionary called dialogues. As we can see in the fifth and other dialogues, the Indian speaks with the words of a Christian theologian, and his lack of trust in himself as God’s creature rightfully recognized by other Christians turns into a lack of trust in the faith and virtuousness of other Christians. Wilson finishes the book with a large number of meditations and prayers meant for families and individual piousness.

Ca. 1763 a rich Quaker Robert King bought Vassa from Pascal, possibly for the same amount of money (forty pounds). By King’s efforts Vassa was instructed in the assessment of goods transported on ships and office work. In the assessment of goods, not only the changeable relation of their mass, size, and quantity with the ship’s carrying power, but also the impact of the changing conditions of nature on the conditions of trade had to be taken into account. In his autobiography Vassa recounts how on the captain’s orders he bought some turkeys instead of the required bulls, and the turkeys survived through the storm and were later sold to good profit. While serving on King’s ships in the Caribbean and receiving more meal money than other slaves, Vassa used to buy fruits, vegetables, and other small goods, and later sell them, and thus in the course of three years he saved enough funds to be able to ask King to sell him his freedom. In 1766 Vassa bought himself out from slavery for the same amount of money for which he had been purchased, and several years later returned to London to ask Pascal for the money, for which the latter had sold him.

In London in February 1768 Vassa celebrated the success of the experiments of his new employee, doctor Charles Irving, in turning seawater into drinking water. Vassa accompanied Irving on two of his trips. In the summer of 1773 he took part in the Royal Expedition to the Arctic, during which a new water route to India was explored. On this expedition Vassa faced the threat of death for the first time, which caused him horror. In the summer of 1775 the second expedition organized by Irving himself took place. His master was set to establish a plantation in Central America, in the territory of the Mosquito Indians, and Vassa went on this journey with missionary goals, planning to convert the Mosquito Indians to the Christian faith. After the occurrence during the expedition to the Arctic Vassa’s religious motivation was becoming more and more obvious. In 1777 Vassa attempted to leave the Mosquito coast and the Caribbean three times, but each time, having embarked as a passenger, was made to stay on board as a slave or sailor under the threat of being killed. The first and greatest disturbance arose on the ship of merchant Hughes, when Vassa, confronted with the threat of losing his freedom, defamed the owner and his team with the same words, which Thomas Wilson used to express his indignation at the Christians in the voice of an Indian who had already mastered a bit of the theological vernacular.

In 1786, botanist Henry Smeathman, known in the world of science at that time for his study on the features of termites living in the hot climatic zones published in 1781, presented a plan of settling free slaves in Sierra Leone to the Treasury and the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. In October of the same year the Committee appointed Vassa a person in charge of the storage of goods on the ships bound for Sierra Leone. Vassa wrote about the squandering of property and racist hypocrisies, which he encountered while preparing the reports, in his letters published in Public Advertiser in 1786–87. At the end of 1786 Smeathman died, and in March 1787, several weeks before the departure, Vassa’s authorizations were suspended. Due to certain obstacles that arose while collecting the supplies necessary for the journey and settling, the ships left the port of Portsmouth much later than was planned. On April 7th the ships filled with free slaves and a great many white prostitutes left for Sierra Leone. Due to the scanty food supplies, standing idle, diseases, and a difficult journey, a considerable part of the colonists did not reach Africa, and when the remainder finally arrived in the territory of the Free Province in Sierra Leone, the rain season started quite soon. A new wave of slaves-colonists that reached the country in 1792 found as few as 64 newcomers from the first expedition, with whom they built the Free City.

In the same year the fifth edition of Vassa’s autobiography appeared, and Gustav Vasa III was killed in Stockholm Royal Opera; his death inspired Giuseppe Verdi to create the opera in three acts Un Ballo in Maschera.

Auridas Gajauskas

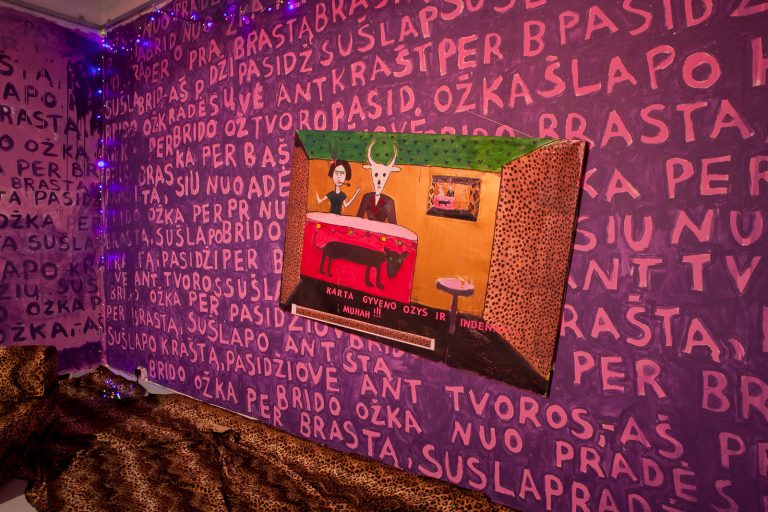

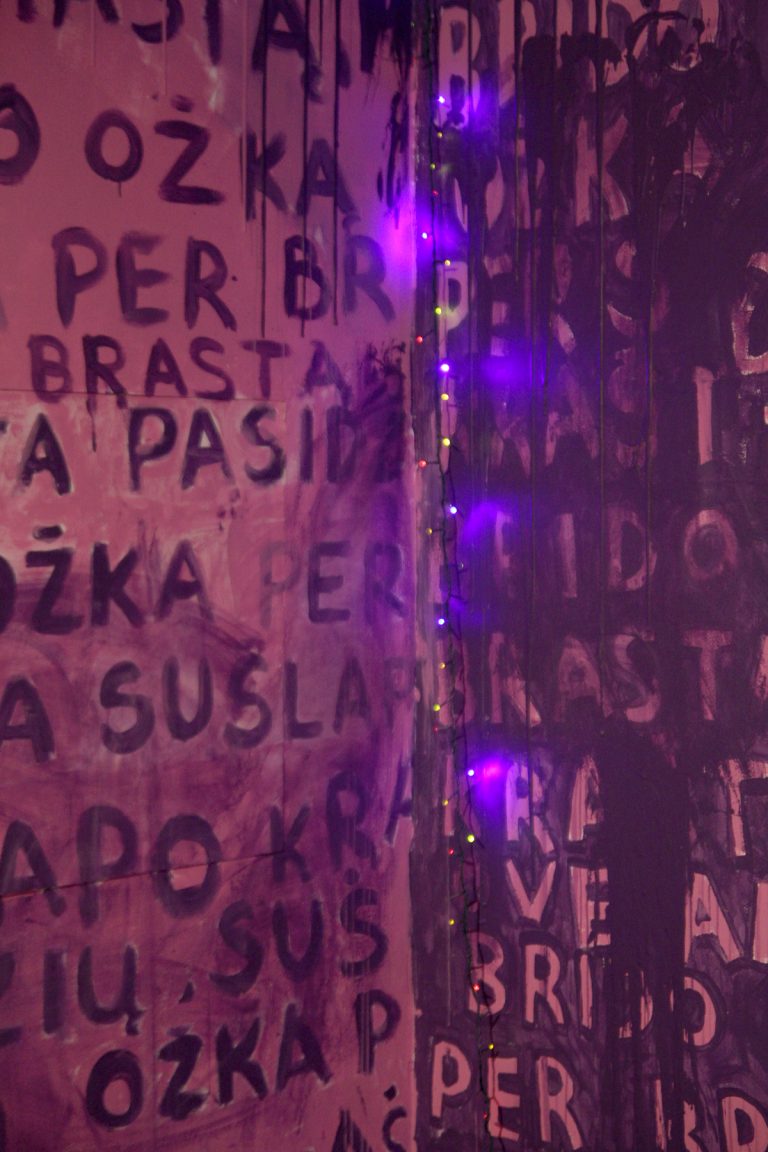

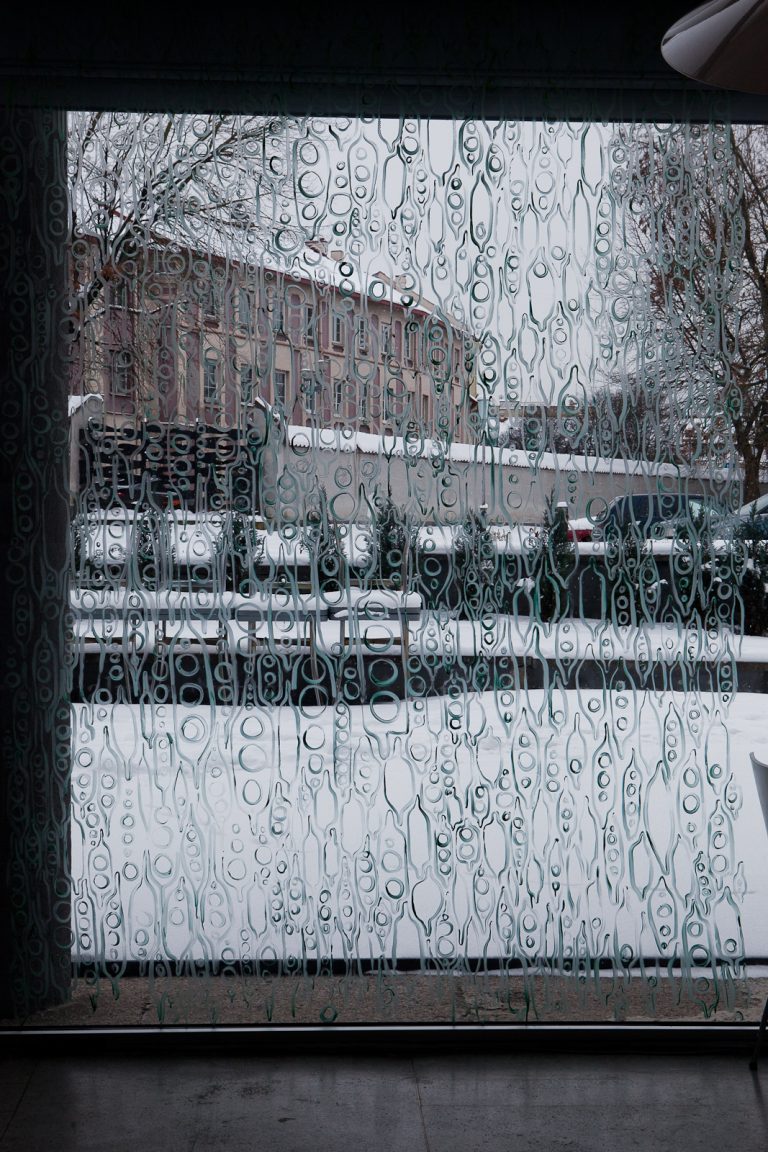

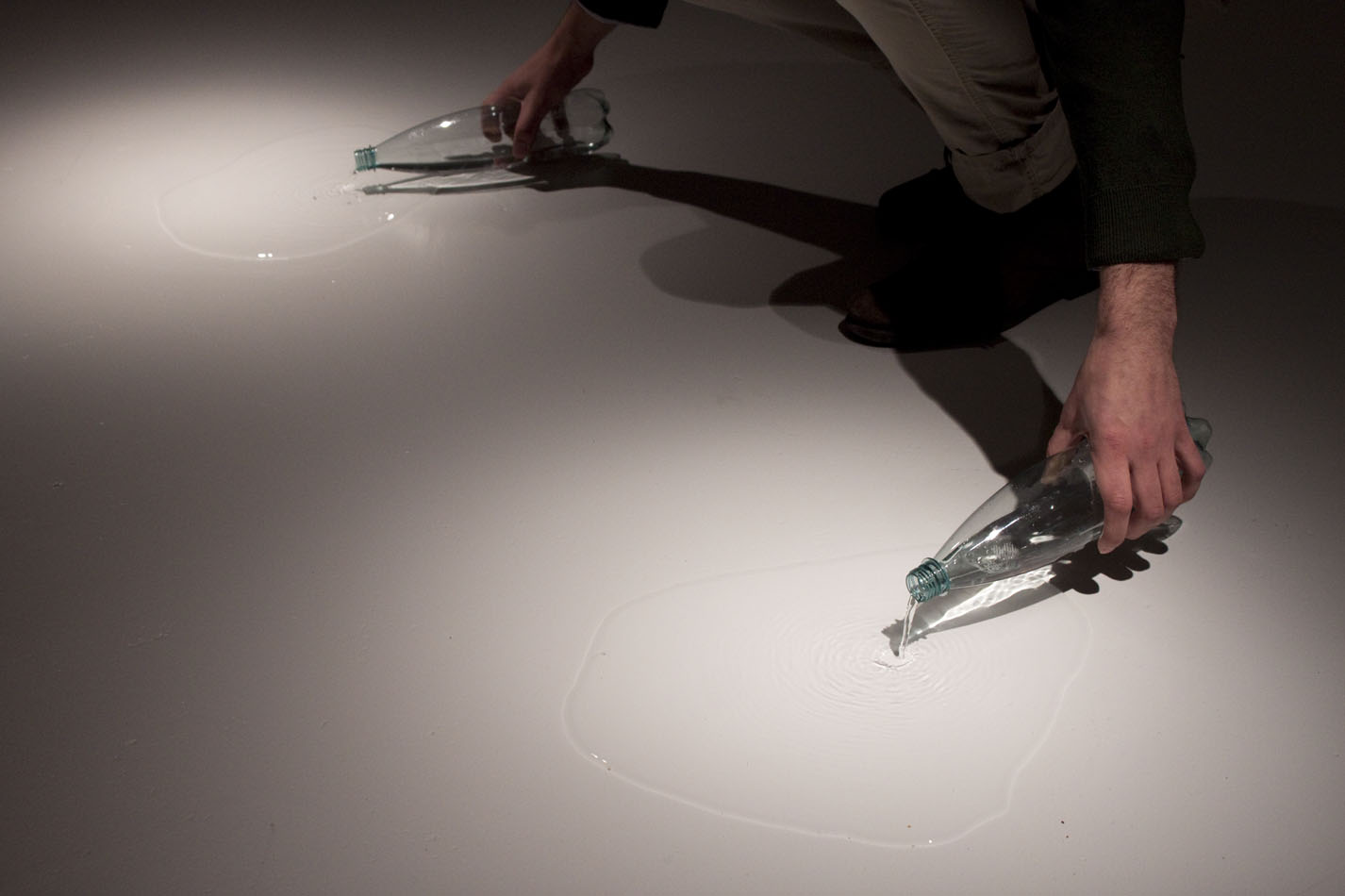

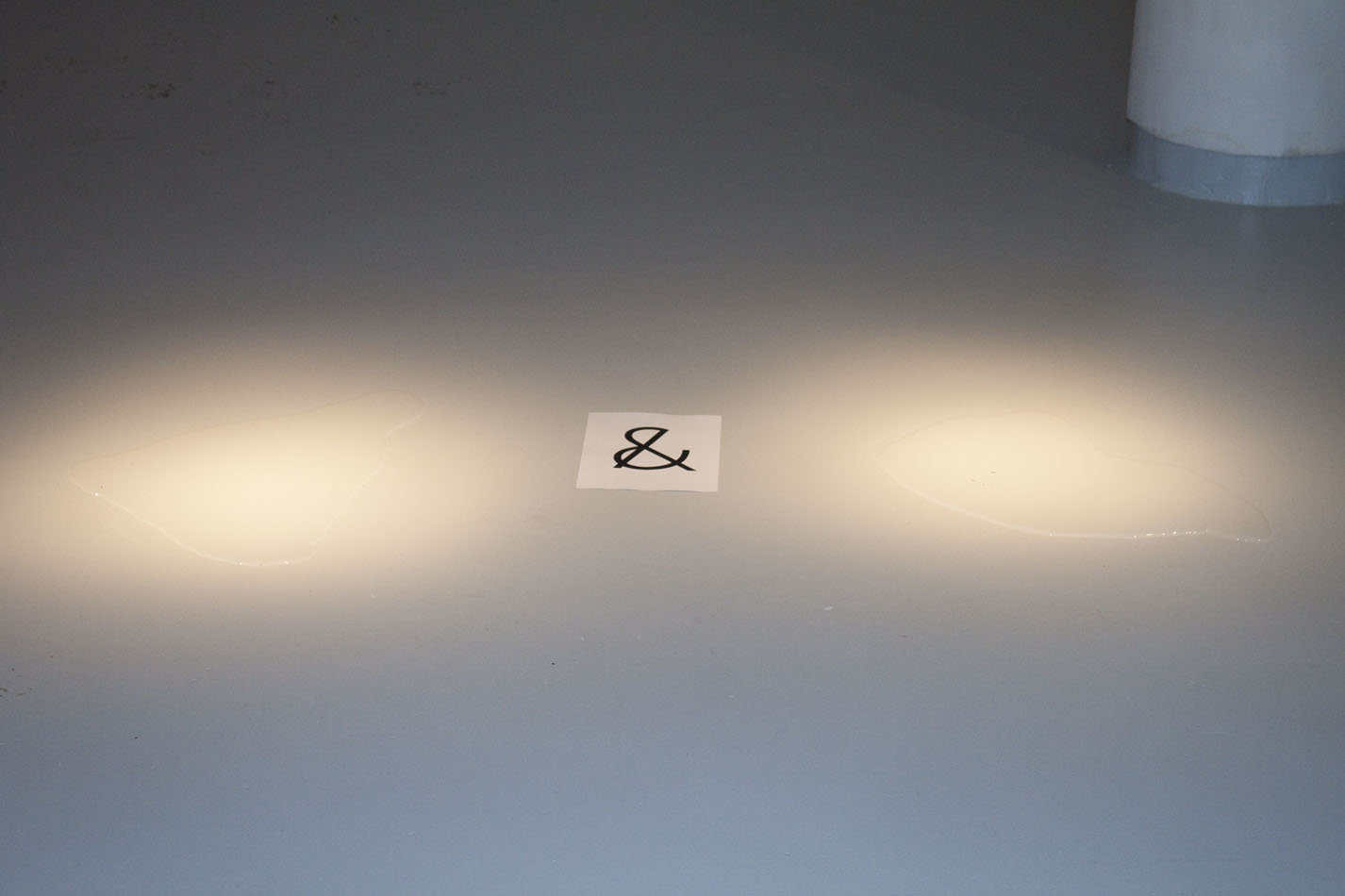

Illustration: photograph from Jonas Žakaitis’s archive