On 2 and 9 December 2023, the film programme about Palestine ‘Kitokia valia’ (A Different Will), organised by the Contemporary Art Centre, the education and media research space Meno avilys, and the cultural organisation artnews.lt, and curated by Edvardas Šumila from the CAC, was screened in Vilnius. The selected films delve into the history of Palestine and the Palestinian-Israeli confrontation by exploring everyday life experiences and going into the stories and narratives of individuals. In this way, a space is (re)created in which our relationship with these themes is not limited to hasty assessments and casualty figures, but also includes the human dimension of interest, exploration and relationships. One of the films shown on December 2nd was “Gaza Calling” (2012). Tadas Zaronskis had an interview with its director Nahed Awwad, which was published on the portal echogonewrong.com.

Nahed Awwad is a Palestinian film director currently based in Berlin. She has produced two feature-length and five short documentaries, and contributes to curating exhibitions. Her films have been screened at many international film festivals, including the HotDocs Film Festival in Canada, the Prague Human Rights Film Festival, and the Vision du réel Film Festival in Switzerland. Nahed Awwad’s documentary filmmaking is characterised by a close, intimate relationship with her characters and her environment. All her work focuses on Palestine, and in one interview she admits that it is impossible to make a film about Palestine that is not political. Thus, her cinema is definitely political, but in no way didactic.

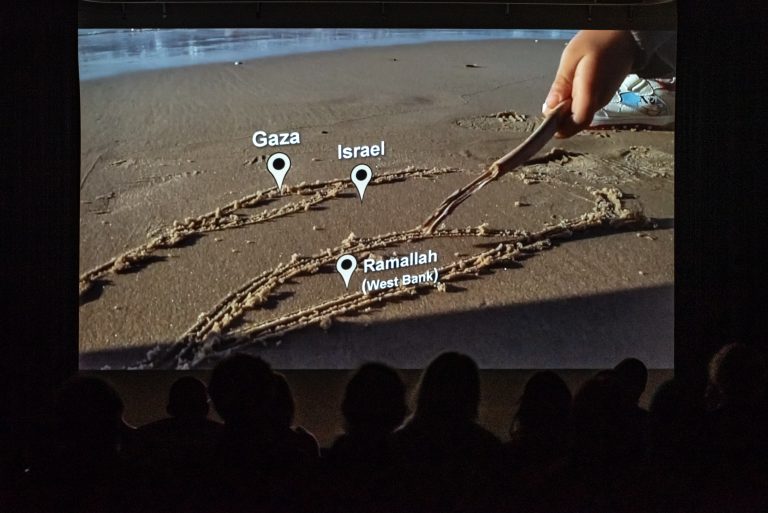

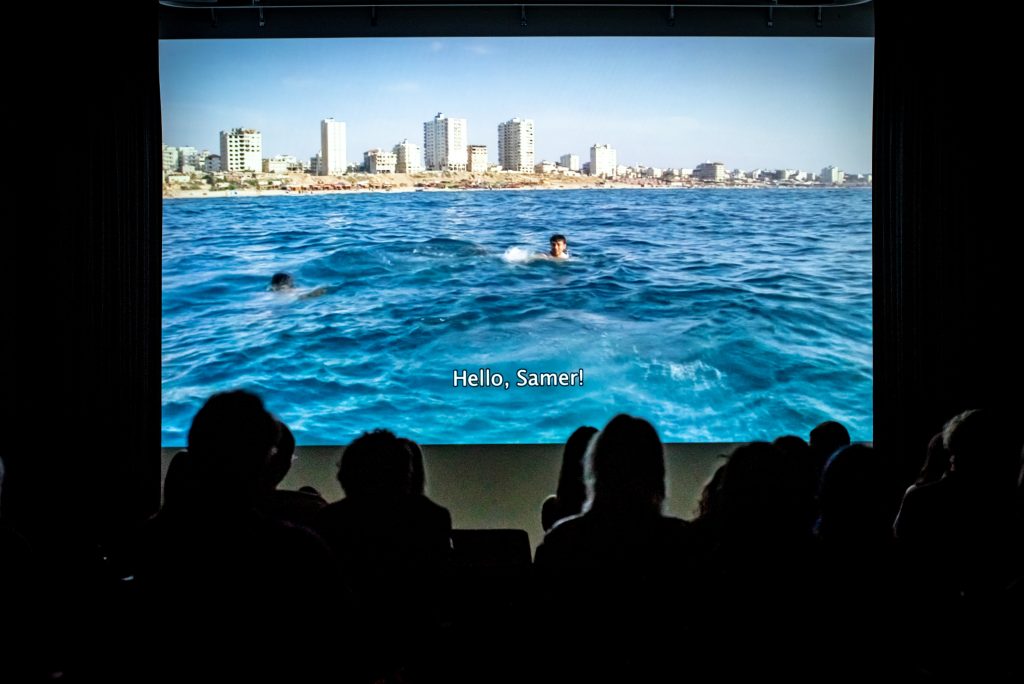

Awwad’s first two works were experimental short films. Lions (2002) and Going for a Ride? (2003) feature images of the 2002 Israeli invasion of the West Bank. Images of destroyed buildings and tanks driving over cars are soon followed by footage of people cleaning the streets, playing music and protesting. These painful and complex realities are presented through the somewhat warm gaze of a local resident. Awwad’s film Gaza Calling, screened as part of the A Different Will programme, follows closely two families. Due to the severe restrictions imposed by Israel on movement between Gaza and the West Bank in 2006, members of these families are torn apart. Although separated by only an hour’s drive, they had not been able to meet for six years by the time of the film’s production in 2012.

Samer, one of the characters in the film, stays in Ramallah after his studies to find better job opportunities in order to help his family in Gaza financially. However, unable to see his relatives and his little sister, who was born after his departure, he becomes gradually depressed. There are countless such cases. Following the two families’ persistent efforts to keep in touch, and exposing the absurdity of life created by arbitrary militarised rules, Awwad develops a coherent political critique based not on theses and slogans, but on allowing people into her world, sharing the lived experience of perseverance and frustration.

Tadas Zaronskis: The screening of your movie Gaza Calling (2012) in Vilnius on 2 December, along with other Palestinian movies, intervenes in the terrible context of an unprecedented escalation of violence. While most human rights organisations warn about the ethnic cleansing happening in Gaza, the international community seems to be slow in taking action to help end the hostilities. In Vilnius, the Palestinian film programme was organised in the context of a rather one-sided right-wing mainstream media discourse, which tends to ignore the wider context of the Palestinian occupation. Gaza Calling was also screened in Berlin (where you live) on 26 October in a similar context of a hegemonic one-sided German-state discourse. How do you see the role of Palestinian art, and particularly the screening of your movies, in this moment of extreme tension and polarisation?

Nahed Awwad : It’s very important. Actually, my film was shown three times recently, in Berlin and in Brandenburg. These events attracted some people who are new to the topic, especially young people, who wanted to learn more, to understand the context of what is happening. This is good. But right now, I feel this is not enough. I want to go on to the streets to demonstrate, public interventions, all these actions are important because in Germany, and actually in most of the Western media, they are not saying enough about what’s happening. The discourse is one-sided. When they talk about Palestinians, it is only numbers. Of course, that’s also because journalists are not allowed by the Israeli army to go into Gaza. And it is so important, because people don’t know what’s really happening. The Israeli narrative is very dominant in the mainstream media, and also among politicians. So we really need to work harder, also by showing our films and art.

And there is lots of movement, actually. In Berlin there are so many events about Palestine, film screenings and discussions, almost every day, or at least two or three times a week. And that’s also because people really want to understand. Social media helps: people notice the difference between what the mainstream media reports about Palestine and the information they are able to gather in social media, from activists or from Palestinians themselves. These two different worlds are parallel to each other. People are clever, especially young people, and they notice that there is something wrong with how things are reported, and they question it. I feel Palestinian art is a very good ambassador for Palestine. It has been doing a really good job, even better than some Palestinian politicians.

TZ: In Germany, where you live, we have recently witnessed two significant attempts to exclude Palestinian, or simply critical, intellectuals and artists. In October, the Frankfurt Book Fair suspended the LiBeraturpreis award ceremony for Adania Shibli for her book Minor Detail. On 16 December, Masha Gessen, an American journalist of Jewish and Russian descent, was awarded the Hannah Arendt prize for political thought. But the event almost did not take place, as the Heinrich Böll Foundation was going to withdraw its support after Gessen recently compared Gaza to the Jewish ghettos of occupied Europe during the Second World War.

How do you feel as a Palestinian artist creating and showing your work in this context? Do you consider it important to fight for the visibility of Palestinian art in the West? Does it affect the relationship with the artistic or intellectual work itself?

NA: I heard about these two incidents, of course, and it’s really sad. I don’t understand it, because we’re supposed to be in a free, democratic country with free speech. But it seems this applies to many things except Palestine. Regarding Adania, her book was already translated into German, published by a German publisher more than a year ago. And all of a sudden, they made this strange decision. This is problematic, because I think one needs to take a stand. If you don’t want to take a stand for Palestine, you should take a stand for freedom of speech, artistic freedom, against censorship. This is art. It doesn’t kill anybody. You know, words don’t kill anybody; it’s bombs that kill people. So it really is ironic what we are seeing.

What happened with Adania also put the spotlight on her book, it sold more because people were interested in why someone was trying to exclude it. From what I have heard, it recently also got translated into more languages. I still can’t understand by what logic they legitimise these actions. As a Palestinian artist, you expect to get cancelled, that your work won’t be shown in the main spaces, that you won’t get state funding.

This is also what is happening in Berlin. So people look for alternative underground places, cafes and bars, where they can show their work. It’s sad, it’s as if the state doesn’t want us to be able to exhibit our art. They also often ask Palestinian artists to condemn their own identity in order to fit into the mainstream-approved narrative. It’s sad, and it makes me angry sometimes.

TZ: Your movie Gaza Calling (2012) focuses on the restriction of a fundamental human freedom, freedom of movement. The camera follows two families that cannot meet any more because of the restrictions on movement between two parts of Palestine (Gaza and the West Bank) imposed by Israel since 2006. But the topic of freedom of movement seems central in your cinema almost from the very beginning. In your other full-length movie Five Minutes from Home (2008), you investigate the Al-Quds airport, which was used for international travel by Palestinians in the 1950s and 1960s, before its occupation by Israel in 1967. Your second short movie Going for a Ride? (2003, in collaboration with an installation by Vera Tamari) shows massive lines of cars crushed by Israeli tanks during the 2002 invasion of Ramallah. So it not only documents violence, but also stresses a particular dimension of it, attacking the very material possibility to move freely. In Not just any Sea! (2006) you protest against the impossibility for people trapped in the West Bank to go to the sea.

How did the topic of freedom of movement become central in your work? Does this topic capture something specific about the violence of occupation which is imposed on the Palestinians?

NA: Actually, it is not intentional, I only noticed it years later. A close friend of mine told me that I was always going back to the same theme. It is a kind of urge for me. I lived in confined places with restricted movement, it was affecting my life and the lives of everybody around me. I felt I needed to show it.

The story of the Jerusalem airport came to me by accident while I was filming The fourth Room (2005). I was talking to Abu Jameel, a character in the film. I asked him how he used to bring books for his bookshop, and he told me he went to Cairo and Beirut every week. And I asked how. And he said he took the plane, from the airport. I come from a generation that thought the airport had always been Israeli. I didn’t even know much about it, because it was always behind a fence, and later behind a wall. I didn’t know that it used to be Palestinian, that it was built during Jordanian times, that most of the workers were Palestinians. This conversation led to me creating Five Minutes from Home.

In general, with my films, when something bothers me or touches me, I feel the need to do something about it. It is the same with Going for a Ride? During the invasion of 2002, I was filming a lot in my neighbourhood and in my city. For some reason, I was focusing on filming those destroyed cars. I was walking around and I saw them. I was naturally drawn to them. So I filmed the cars even before I knew that the artist Vera Tamari was making her installation with those smashed cars. I learned about it by accident from a colleague of mine who was working on the idea with her. So I wanted to meet her, and we did, and then we decided that it would be a good collaboration. I already had some footage, and she wanted me to document the installation.

I lived in Ramallah, but my family lived in Bethlehem. So I was moving between the two cities a lot. And there were always obstacles, checkpoints. We often had to change our route. That is something I was affected by. And I wanted to do something to reflect it, and to share it with people.

TZ: Another very significant topic in your cinema is the relationship with memory and the past. Time in your movies often seems to be cut between ‘then’ and ‘now’. In Five Minutes from Home it is the past, when international travel was freely accessible to Palestinians, that you explore as something forgotten, almost unimaginable for the current generation. In The Fourth Room (2005) you interview Abu Jamil, who talks about the ‘good old times’ before the occupation, before the checkpoints, when he could move freely. He preserves signs and memories of those times: a red car parked in front of his home, even though it doesn’t work any more. In Gaza Calling, time is also broken in two: before 2006, when Israel imposed strict control over movement between Gaza and the West Bank, and afterwards. It is as if you try to gather the pieces of a better past, in order for it not to be buried under the rubble of the present. How do you understand this relationship with the past? Can it be called nostalgia, or is it something else? Why is the work of memory important in your cinema?

NA: Yes, part of it is nostalgia, but only part. It’s important to document the situation in Palestine, because the landscape, the space, everything is changing rapidly. I noticed it especially when I started travelling outside Palestine and coming back. Because of the occupation, land is being confiscated, fences and walls for segregation are being built. It is my childhood landscape that is being changed, and I have always felt the urge to document it, to film it. Every time I go to Palestine, I take a camera with me, and I film because I don’t know if next time I visit it will still be there.

People are always losing land, so, for example, in Bethlehem, where my family lives, the city is cut off, from three sides, by a wall of Israeli settlements. People are getting married, they need space for their families, so they build vertically, additional floors, because they can’t expand horizontally. I feel I need to capture that as well.

It is important for me as a form of protest against a reality that I don’t really accept. I need to capture how it used to be, how it is, because people without memory are like a computer, an empty machine.

Many times, the Israeli army tried to destroy it. In 1948, they confiscated whole libraries and photographic archives. They did it again in 1967, and again in Beirut in 1982, then again in the 2002 invasion of the West Bank. That time they went into my office, where I worked in a television station in Ramallah. They took many things, including hard drives. So we resist by preserving the memory, not only for us, but also for future generations. I recognise this effort in many Palestinian artists and filmmakers.

To preserve the memory also means to be able to present another narrative, our narrative, which is absent from the mainstream media, but you can find it in many alternative places, and also in universities. They cannot bury everything.

TZ: You talk about preserving memory as an act of resistance, and another aspect of your cinema seems to me to be related to this topic. You have a very intimate relationship with the people you film. In one interview you mention that it is different to working with actors. Watching Gaza Calling I was almost astonished by how accepting people were of the camera, gently letting you into their lives. Also, your movies are about your own home and the violence it suffers. I don’t know if I can say it, but I have the impression that even the terrible violence that you document becomes in a sense intimate in your movies. In your first movie, Lions, the gaze of the camera is not that of a journalist documenting a tragedy, but more like the gaze of someone who lives there, who is comfortable with the space. How does it change the cinema you make? Does this intimate relationship with what you film change the very genre of your films, or their production process?

NA: I make films about people I know and places that are familiar to me. It’s very important. So, for example, in the movie Lions I film a destroyed restaurant, and I’ve been to that restaurant. You can see the sign ‘For family’ in the rubble, and I remember that sign. It is the same, for example, with Samer, who I film in Gaza Calling. He is actually a relative of a friend and colleague. I already knew him, but in all cases it is important for me to build a relationship with the people I film.

And sometimes this makes it hard. Samer was living in the West Bank, and he decided to go back to Gaza. You see it in the movie. After his decision, when we weren’t filming, I asked him, are you sure? Do you really understand what it means? In the film it was a very good scene, when he goes back. But at the same time, it is really hard to hold these two roles together, being a filmmaker, but also a human being who cares about Samer, who considers him a friend and likes him. I’m still in contact with Samer, he’s in Gaza now. He’s married with two beautiful daughters. I’m really worried about him and his family. I write to him, sometimes he takes a few days to answer. But I also feel ashamed or shy to write him. What shall I ask him? Are you still alive? So sometimes I ask his cousin in London or his brother in Paris. I know Samer and his family are fine, but they are also not fine; mentally, they are exhausted to the limit. All they need now is a ceasefire, this needs to be stopped, and not just for a break.

TZ: In Gaza Calling I found one moment involving Samer particularly touching. Samer is a young camera operator who stayed in Ramallah after his studies to work for a news agency and wasn’t able to see his family (who live in Gaza), or the sea, for six years. As you mentioned, at one point he decides to abandon his work and go back to Gaza. This is a sort of sacrifice, since the work prospects are worse there, life is more dangerous, and he will probably not be able to leave. But in the car which transports him through Israeli territory to the checkpoint, he looks to the hills and says: ‘We have a beautiful country.’ This seems to be a moment of freedom and hope. In the midst of total unfreedom, for a moment, freedom of movement is reclaimed, even if in a very restricted way. In Gaza Calling both families fight to keep in contact, they call each other, send video recordings and gifts, and appeal to NGOs. In Lions the images of destruction are juxtaposed with those of people tidying up the rubble, a man playing music in the street, and a demonstration where Palestinians are seen chanting: ‘We want to live in freedom!’ These moments of resistance and hope are very present in your movies. Do you see your cinema as hopeful?

NA: First, thanks for your words, and for noticing these little things, because not everybody sees them. I’m somebody who’s hopeful despite the darkness, and my cinema reflects it. I always look for human connection, and for these little moments that give hope, firstly to me and then to the audience. Hope that helps one keep resisting injustice and making films about it, even though it becomes really dark and frustrating sometimes. We are only humans, you know. Like Samer and his decision, it was very hard for him. But he wanted to be with his family, he chose it, and I respect that. I think if he stayed in Ramallah, maybe he would be very miserable. Especially now, with what’s happening in Gaza, I can’t imagine it. I have lots of friends who have families in Gaza, and they’re really living through hell. They cannot function well: always watching the news, always trying to call their families. They feel helpless. But also I feel that we, who live outside Palestine, have to keep fighting, with all the tools we have, like art, films and words, for those who are in Palestine.

The people who come to events about Palestine in Berlin, it’s a really colourful crowd, different ethnicities and backgrounds. It’s so empowering and hopeful to see these kinds of people show their support and call for a ceasefire. I hope for a ceasefire very, very soon, even today. It will take years to rebuild Gaza. The people there have been through hell, and we need to continue to support them, to bring their voice out in many shapes, as artists and activists can do.